Crescimento e extinção da população humana

A extinção em massa atual difere de todas as outras por ser impulsionada por uma única espécie, em vez de um processo físico planetário ou galáctico. Quando a raça humana - Homo sapiens sapiens - migrou da África para o Oriente Médio há 90.000 anos, para a Europa e Austrália há 40.000 anos, para a América do Norte 12.500 anos atrás e para o Caribe 8.000 anos atrás, ondas de extinção logo se seguiram. O padrão de colonização seguida de extinção pode ser visto até 2.000 anos atrás, quando os humanos colonizaram Madagascar e rapidamente extinguiram pássaros elefantes, hipopótamos e grandes lêmures [1].

Lange's metalmark butterfly from Amy Harwood.

A primeira onda de extinções teve como alvo grandes vertebrados caçados por caçadores-coletores. A segunda onda, maior, começou há 10.000 anos, quando a descoberta da agricultura causou um boom populacional e a necessidade de arar os habitats da vida selvagem, desviar riachos e manter grandes rebanhos de gado doméstico. A terceira e maior onda começou em 1800 com o aproveitamento de combustíveis fósseis. Com energia enorme e barata à sua disposição, a população humana cresceu rapidamente de 1 bilhão em 1800 para 2 bilhões em 1930, 4 bilhões em 1975 e mais de 7,5 bilhões hoje. Se o curso atual não for alterado, chegaremos a 8 bilhões em 2020 e de 9 a 15 bilhões (provavelmente o primeiro) em 2050.

Nenhuma população de um grande animal vertebrado na história do planeta cresceu tanto, tão rápido, ou com consequências tão devastadoras para seus companheiros terrestres. O impacto sobre os humanos foi tão profundo que os cientistas propuseram que a era do Holoceno fosse declarada encerrada e a época atual (começando por volta de 1900) fosse chamada de Antropoceno: a era em que os "efeitos ambientais globais do aumento da população humana e do desenvolvimento econômico" dominam condições planetárias físicas, químicas e biológicas [2].

- Humans annually absorb 42 percent of the Earth’s terrestrial net primary productivity,30 percent of its marine net primary productivity, and 50 percent of its fresh water [3].

- Forty percent of the planet’s land is devoted to human food production, up from 7 percent in 1700 [3].

- Fifty percent of the planet’s land mass has been transformed for human use [3].

- More atmospheric nitrogen is now fixed by humans that all other natural processes combined [3].

The authors of Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems, including the current director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, concluded:

"[A]ll of these seemingly disparate phenomena trace to a single cause: the growing scale of the human enterprise. The rates, scales, kinds, and combinations of changes occurring now are fundamentally different from those at any other time in history. . . . We live on a human-dominated planet and the momentum of human population growth, together with the imperative for further economic development in most

of the world, ensures that our dominance will increase."

Predicting local extinction rates is complex due to differences in biological diversity, species distribution, climate, vegetation, habitat threats, invasive species, consumption patterns, and enacted conservation measures. One constant, however, is human population pressure. A study of 114 nations found that human population density predicted with 88-percent accuracy the number of endangered birds and mammals as identified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature [4]. Current population growth trends indicate that the number of threatened species will increase by 7 percent over the next 20 years and 14 percent by 2050. And that’s without the addition of global warming impacts.

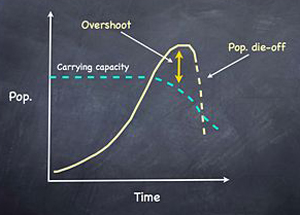

When the population of a species grows beyond the capacity of its environment to sustain it, it reduces that capacity below the original level, ensuring an eventual population crash.

"The density of people is a key factor in species threats," said Jeffrey McKee, one of the study’s authors. "If other species follow the same pattern as the mammals and birds... we are facing a serious threat to global biodiversity associated with our growing human population." [5].

So where does wildlife stand today in relation to 7.5 billion people? Worldwide, 12 percent of mammals, 12 percent of birds, 31 percent of reptiles, 30 percent of amphibians, and 37 percent of fish are threatened with extinction [6]. Not enough plants and invertebrates have been assessed to determine their global threat level, but it is severe.

Extinction is the most serious, utterly irreversible effect of unsustainable human population. But unfortunately, many analyses of what a sustainable human population level would look like presume that the goal is simply to keep the human race at a level where it has enough food and clean water to survive. Our notion of sustainability and ecological footprint — indeed, our notion of world worth living in — presumes that humans will allow for, and themselves enjoy, enough room and resources for all species to live.

REFERENCES CITED

- Eldridge, N. 2005. The Sixth Extinction. ActionBioscience.org.

- Crutzen, P. J. and E. F. Stoermer. 2000. The 'Anthropocene'. Global Change Newsletter 41:17–18, 2000; Zalasiewicz, J. et al. 2008. Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene?. GSA Today (Geological Society of America) 18 (2): 4–8.

- Vitousek, P. M., H. A. Mooney, J. Lubchenco, and J. M. Melillo. 1997. Human Domination of Earth's Ecosystems. Science 277 (5325): 494–499; Pimm, S. L. 2001. The World According to Pimm: a Scientist Audits the Earth. McGraw-Hill, NY; The Guardian. 2005. Earth is All Out of New Farmland. December 7, 2005.

- McKee, J. K., P. W. Sciulli, C. D. Fooce, and T. A. Waite. 2004. Forecasting Biodiversity Threats Due to Human Population Growth. Biological Conservation 115(1): 161–164.

- Ohio State University. 2003. Anthropologist Predicts Major Threat To Species Within 50 Years. ScienceDaily, June 10, 2003.

- International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 2009. Red List.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.