Fossilized skin reveals coevolution with feathers and metabolism in feathered dinosaurs and early birds

Abstract

Feathers

are remarkable evolutionary innovations that are associated with

complex adaptations of the skin in modern birds. Fossilised feathers in

non-avian dinosaurs and basal birds provide insights into feather

evolution, but how associated integumentary adaptations evolved is

unclear. Here we report the discovery of fossil skin, preserved with

remarkable nanoscale fidelity, in three non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs

and a basal bird from the Cretaceous Jehol biota (China). The skin

comprises patches of desquamating epidermal corneocytes that preserve

a cytoskeletal array of helically coiled α-keratin tonofibrils. This

structure confirms that basal birds and non-avian dinosaurs shed small

epidermal flakes as in modern mammals and birds, but structural

differences imply that these Cretaceous taxa had lower body heat

production than modern birds. Feathered epidermis acquired many, but not

all, anatomically modern attributes close to the base of the

Maniraptora by the Middle Jurassic.

Introduction

The

integument of vertebrates is a complex multilayered organ with

essential functions in homoeostasis, resisting mechanical stress and

preventing pathogenic attack1.

Its evolution is characterised by recurrent anatomical innovation of

novel tissue structures (e.g., scales, feathers and hair) that, in

amniotes, are linked to major evolutionary radiations2. Feathers are associated with structural, biochemical and functional modifications of the skin2, including a lipid-rich corneous layer characterised by continuous shedding3. Evo-devo studies4 and fossilised feathers5,6,7

have illuminated aspects of early feather evolution, but how the skin

of basal birds and feathered non-avian dinosaurs evolved in tandem with

feathers has received little attention. Like mammal hair, the skin of

birds is thinner than in most reptiles and is shed in millimetre- scale

flakes (comprising shed corneocytes, i.e., terminally differentiated

keratinocytes), not as large patches or a whole skin moult2.

Desquamation of small patches of corneocytes, however, also occurs in

crocodilians and chelonians and is considered primitive to synchronised

cyclical skin shedding in squamates8.

Crocodilians and birds, the groups that phylogenetically bracket

non-avian dinosaurs, both possess the basal condition; parsimony

suggests that this skin shedding mechanism was shared with non-avian

dinosaurs.

During dinosaur evolution, the increase in metabolic rate towards a true endothermic physiology (as in modern birds) was associated with profound changes in integument structure9 relating to a subcutaneous hydraulic skeletal system, an intricate dermo-subcutaneous muscle system, and a lipid-rich corneous layer characterised by continuous shedding3.

The pattern and timing of acquisition of these ultrastructural skin characters, however, is poorly resolved and there is no a priori reason to assume that the ultrastructure of the skin of feathered non-avian dinosaurs and early birds would have resembled that of their modern counterparts. Dinosaur skin is usually preserved as an external mould10 and rarely as organic remains11,12 or in authigenic minerals13,14,15. Although mineralised fossil skin can retain (sub-)cellular anatomical features16,17, dinosaur skin is rarely investigated at the ultrastructural level14. Critically, despite reports of preserved epidermis in a non-feathered dinosaur10 there is no known evidence of the epidermis18 in basal birds or of preserved skin in feathered non-avian dinosaurs. The coevolutionary history of skin and feathers is therefore largely unknown.

Here we report the discovery of fossilised skin in the feathered non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs Beipiaosaurus, Sinornithosaurus and Microraptor, and the bird Confuciusornis from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota (NE China; Supplementary Fig. 1). The ultrastructure of the preserved tissues reveals that feathered skin had evolved many, but not all, modern attributes by the origin of the Maniraptora in the Middle Jurassic.

During dinosaur evolution, the increase in metabolic rate towards a true endothermic physiology (as in modern birds) was associated with profound changes in integument structure9 relating to a subcutaneous hydraulic skeletal system, an intricate dermo-subcutaneous muscle system, and a lipid-rich corneous layer characterised by continuous shedding3.

The pattern and timing of acquisition of these ultrastructural skin characters, however, is poorly resolved and there is no a priori reason to assume that the ultrastructure of the skin of feathered non-avian dinosaurs and early birds would have resembled that of their modern counterparts. Dinosaur skin is usually preserved as an external mould10 and rarely as organic remains11,12 or in authigenic minerals13,14,15. Although mineralised fossil skin can retain (sub-)cellular anatomical features16,17, dinosaur skin is rarely investigated at the ultrastructural level14. Critically, despite reports of preserved epidermis in a non-feathered dinosaur10 there is no known evidence of the epidermis18 in basal birds or of preserved skin in feathered non-avian dinosaurs. The coevolutionary history of skin and feathers is therefore largely unknown.

Here we report the discovery of fossilised skin in the feathered non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs Beipiaosaurus, Sinornithosaurus and Microraptor, and the bird Confuciusornis from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota (NE China; Supplementary Fig. 1). The ultrastructure of the preserved tissues reveals that feathered skin had evolved many, but not all, modern attributes by the origin of the Maniraptora in the Middle Jurassic.

Results and discussion

Fossil soft tissue structure

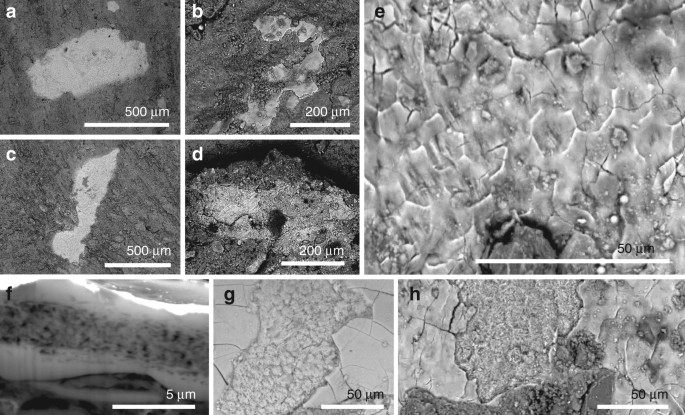

Small patches of tissue (0.01–0.4 mm2; Fig. 1a–d and Supplementary Figs. 2–6) are closely associated with fossil feathers (i.e., usually within 500 µm of carbonaceous feather residues, Supplementary Fig. 2e, g, j, k, o, s, t). The patches are definitively of fossil tissue, and do not reflect surface contamination with modern material during sample preparation, as they are preserved in calcium phosphate (see 'Taphonomy', below); further, several samples show margins that are overlapped, in part, by the surrounding matrix. The tissues have not, therefore, simply adhered to the sample surface as a result of contamination from airborne particles in the laboratory.

Phosphatised soft tissues in non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs and a basal bird. a–h Backscatter electron images of tissue in Confuciusornis (IVPP V 13171; a, e, f), Beipiaosaurus (IVPP V STM31-1; b, g), Sinornithosaurus (IVPP V 12811; c, h) and Microraptor (IVPP V 17972A; d). a–d Small irregularly shaped patches of tissue. e Detail of tissue surface showing polygonal texture. f

Focused ion beam-milled vertical section through the soft tissue

showing internal fibrous layer separating two structureless layers. g, h Fractured oblique section through the soft tissues, showing the layers visible in f

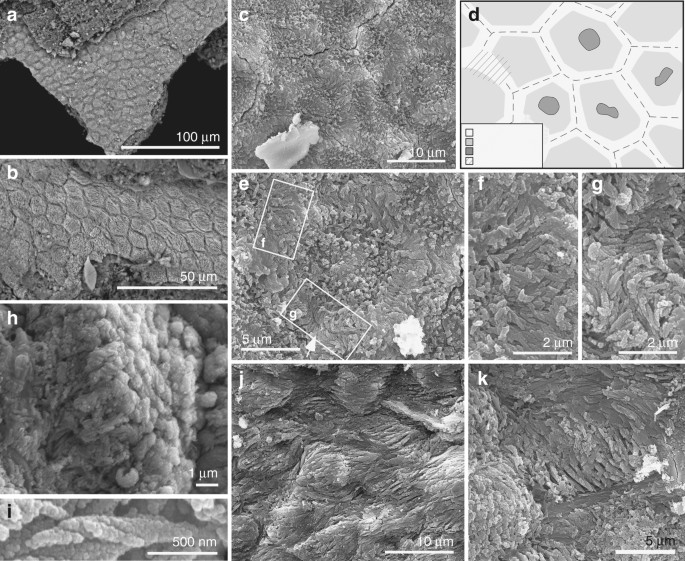

The fibrous layer also shows polygons (Figs. 1f, h and 2a–e, and Supplementary Fig. 6) that contain arrays of densely packed fibres 0.1–0.5 µm wide (Fig. 2f–i and Supplementary Fig. 5f). Well-preserved fibres show helicoidal twisting (Fig. 2h, i). Fibres in marginal parts of each polygon are 0.1–0.3 µm wide and oriented parallel to the tissue surface; those in the interior of each polygon are 0.3–0.5 µm wide and are usually perpendicular to the tissue surface (Fig. 2b, h and Supplementary Fig. S6d). In the marginal 1–2 µm of each polygon, the fibres are usually orthogonal to the lateral polygon margin and terminate at, or bridge the junction between, adjacent polygons (Fig. 2f, g and Supplementary Fig. 6e). The polygons are usually equidimensional but are locally elongated and mutually aligned, where the thick fibres in each polygon are sub-parallel to the tissue surface and the thin fibres, parallel to the polygon margin (Fig. 2j, k and Supplementary Fig. 6g–l). Some polygons show a central depression (Fig. 2c–e and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c) in which the thick fibres can envelop a globular structure 1–2 µm wide (Fig. 2e).

Ultrastructure of the soft tissues in Confuciusornis (IVPP V 13171). a, b Backscatter electron micrographs; all other images are secondary electron micrographs. a, b Closely packed polygons. c Detail of polygons showing fibrous contents, with d interpretative drawing. e–g Polygon (e) with detail of regions indicated showing tonofibrils bridging (f) and abutting at (g) junction between polygons. h, i Helical coiling in tonofibrils. h Oblique view of polygon with central tonofibrils orientated perpendicular to the polygon surface. j, k Polygons showing stretching-like deformation

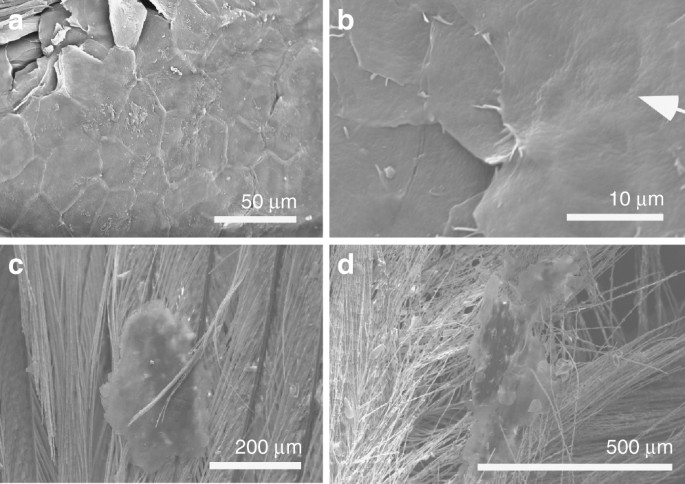

Fossil corneocytes

The texture of these fossil tissues differs from that of conchostracan shells and fish scales from the host sediment, the shell of modern Mytilus, modern and fossil feather rachis and modern reptile epidermis (Supplementary Fig. 7a–n). The elongate geometry of some polygons (Fig. 2j, k and Supplementary Fig. 6g, l) implies elastic deformation of a non-biomineralized tissue due to mechanical stress. On the basis of their size, geometry and internal structure, the polygonal structures are interpreted as corneocytes (epidermal keratinocytes). In modern amniotes, these are polyhedral-flattened cells (1–3 µm × ca. 15 µm) filled with keratin tonofibrils, lipids and matrix proteins18,19,20 (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Figs 2u–x, 8, 9). The outer structureless layer of the fossil material corresponds to the cell margin; it is thicker than the original biological template, i.e., the corneous cell envelope and/or cell membrane, but this is not unexpected, reflecting diagenetic overgrowth by calcium phosphate (see 'Taphonomy'). The fibres in the fossil corneocytes are identified as mineralised tonofibrils: straight, unbranching bundles of supercoiled α-keratin fibrils 0.25–1 µm wide18,21 that are the main component of the corneocyte cytoskeleton22 and are enveloped by amorphous cytoskeletal proteins22. In the fossils, the thin tonofibrils often abut those of the adjacent cell (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 6e), but locally can bridge the boundary between adjacent cells (Fig. 2f). The latter recalls desmosomes, regions of strong intercellular attachment between modern corneocytes23. The central globular structures within the fossil corneocytes resemble dead cell nuclei24, as in corneocytes of extant birds (but not extant reptiles and mammals)24 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The position of these pycnotic nuclei is often indicated by depressions in the corneocyte surface in extant birds24 (Fig. 3b); some fossil cells show similar depressions (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c).Taphonomy

Keratin is a relatively recalcitrant biomolecule due to its heavily cross-linked paracrystalline structure and hydrophobic nonpolar character23. Replication of the fossil corneocytes in calcium phosphate is thus somewhat unexpected as this process usually requires steep geochemical gradients characteristic of early decay25 and usually applies to decay-prone tissues, such as muscle26 and digestive tissues27. Recalcitrant tissues such as dermal collagen can, however, be replicated in calcium phosphate where they contain an inherent source of calcium and, in particular, phosphate ions that are liberated during decay28. Corneocytes contain sources of both of these ions. During terminal differentiation, intracellular concentrations of calcium increase29 and α-keratin chains are extensively phosphorylated23. Further, corneocyte lipid granules30 are rich in phosphorus and phosphate31. These chemical moieties would be released during degradation of the granules and would precipitate on the remaining organic substrate, i.e., the tonofibrils.In extant mammals, densely packed arrays of tonofibrils require abundant interkeratin matrix proteins for stability32. These proteins, however, are not evident in the fossils. This is not unexpected, as the proteins are rare in extant avian corneocytes33 and, critically, occur as dispersed monomers34 and would have a lower preservation potential than the highly cross-linked and polymerised keratin bundles of the tonofibrils. The outer structureless layer of the fossil corneocytes is thicker than the likely biological template(s), i.e., the corneous cell envelope (a layer of lipids, keratin and other proteins up to 100 nm thick that replaces the cell membrane during terminal differentiation34) and/or cell membrane. This may reflect a local microenvironment conducive to precipitation of calcium phosphate: during terminal differentiation, granules of keratohyalin, an extensively phosphorylated protein35 with a high affinity for calcium ions36, accumulate at the periphery of the developing corneocytes37. The thickness of the outer solid layer of calcium phosphate in the fossils, plus the gradual transition from this to the inner fibrous layer, suggests that precipitation of phosphate proceeded from the margins towards the interior of the corneocytes. In this scenario, phosphate availability in the marginal zones of the cells would have exceeded that required to replicate the tonofibrils. The additional phosphate would have precipitated as calcium phosphate in the interstitial spaces between the tonofibrils, progressing inwards from the inner face of the cell margin.

Skin shedding in feathered dinosaurs and early birds

In extant amniotes, the epidermal cornified layer is typically 5–20 cells thick (but thickness varies among species and location on the body38). The patches of fossil corneocytes, however, are one cell thick (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Figs. 5c, 10). This, plus the consistent small size (<400 a="" and="" continuous="" fidelity="" high="" i="" in="" inconsistent="" is="" m="" minority="" nbsp="" of="" patches="" preservation="" remarkably="" selective="" sheet="" situ="" the="" tissue.="" with="">nThe size, irregular geometry and thickness of the patches of corneocytes resemble shed flakes of the cornified layer (dandruff-like particles39; Fig. 3). In extant birds, corneocytes are shed individually or in patches up to 0.5 mm2 that can be entrained within feathers (Fig. 3c, d and Supplementary Fig. 2u, v). The fossils described herein provide the first evidence for the skin shedding process in basal birds and non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs and confirm that at least some non-avian dinosaurs shed their skin in small patches40. This shedding style is identical to that of modern birds18 (Fig. 3c, d) and mammals20 and implies continuous somatic growth. This contrasts with many extant reptiles, e.g., lepidosaurs, which shed their skin whole or in large sections21, but shedding style can be influenced by factors such as diet and environment41.

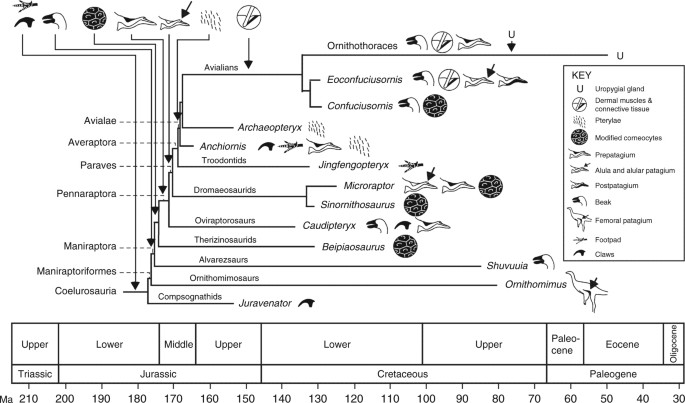

Evolutionary implications of fossil corneocyte structure

The fossil corneocytes exhibit key adaptations found in their counterparts in extant birds and mammals, especially their flattened polygonal geometry and fibrous cell contents consistent with α-keratin tonofibrils16. Further, the fossil tonofibrils (as in extant examples22) show robust intercellular connections and form a continuous scaffold across the corneocyte sheet (Fig. 2b, c, j and Supplementary Fig. 6). In contrast, corneocytes in extant reptiles contain a homogenous mass of β-keratin (with additional proteins present in the cell envelope) and fuse during development, forming mature β-layers without distinct cell boundaries42. The retention of pycnotic nuclei in the fossil corneocytes is a distinctly avian feature not seen in modern reptiles (but see ref. 20).Epidermal morphogenesis and differentiation are considered to have diverged in therapsids and sauropsids31. Our data support other evidence that shared epidermal features in birds and mammals indicate convergent evolution43 and suggest that lipid-rich corneocyte contents may be evolutionarily derived characters in birds and feathered non-avian maniraptorans. Evo-devo studies have suggested that the avian epidermis could have arisen from the expansion of hinge regions in ‘protofeather’-bearing scaly skin20. While fossil evidence for this transition is lacking, our data show that the epidermis of basal birds and non-avian maniraptoran dinosaurs had already evolved a decidedly modern character, even in taxa not capable of powered flight. This does not exclude the possibility that at least some of the epidermal features described here originated in more basal theropods, especially where preserved skin lacks evidence of scales (as in Sciurumimus44). Refined genomic mechanisms for modulating the complex expression of keratin in the epidermis45, terminal differentiation of keratinocytes and the partitioning of α- and β-keratin synthesis in the skin of feathered animals32 were probably modified in tandem with feather evolution close to the base of the Maniraptora by the late Middle Jurassic (Fig. 4). Existing fossil data suggest that this occurred after evolution of the beak in Maniraptoriformes and before evolution of the forelimb patagia and pterylae (Fig. 4); the first fossil occurrences of all of these features span ca. 10–15 Ma, suggesting a burst of innovation in the evolution of feathered integument close to and across the Lower-Middle Jurassic boundary. The earliest evidence for dermal musculature associated with feathers is ca. 30 Ma younger, in a 125 Ma ornithothoracean bird17. Given the essential role played by this dermal network in feather support and control of feather orientation18, its absence in feathered non-avian maniraptorans may reflect a taphonomic bias.

Schematic

phylogeny, scaled to geological time, of selected coelurosaurs showing

the pattern of acquisition of key modifications of the skin. The

phylogeny is the most likely of the maximum likelihood models, based on

minimum-branch lengths (mbl) and transitions occurring as

all-rates-different (ARD). Claws and footpads are considered primitive

in coelurosaurs. Available data indicate that modified keratinocytes,

and continuous shedding, originated close to the base of the

Maniraptora; this is predicted to shift based on future fossil

discoveries towards the base of the Coelurosauria to include other

feathered taxa

Methods

Fossil material

This study used the following specimens in the collections of the Institute for Vertebrate Palaeontology and Paleanthropology, Beijing, China: Confuciusornis (IVPP V 13171), Beipiaosaurus (IVPP V STM31-1), Sinornithosaurus (IVPP V 12811) and Microraptor (IVPP V 17972A). Small (2–10 mm2) chips of soft tissue were removed from densely feathered regions of the body during initial preparation of the specimens and stored for later analysis. Precise sampling locations are not known.Modern bird tissues

Male specimens of the zebra finch Taeniopygia guttata (n = 1) and the Java sparrow Lonchura oryzivora (n = 2) were euthanased via cervical dislocation. Individual feathers dissected from T. guttata and moulted down feathers from a male specimen of the American Pekin duck (Anas platyrhynchos domestica) were not treated further. Small (ca. 10–15 mm2) pieces of skin and underlying muscle tissue were dissected from the pterylae of the breast of reproductively active male specimens of L. oryzivora raised predominantly on a diet of seeds in October 2016. Tissue samples were fixed for 6 h at 4 °C in 4% paraformaldehyde. After snap freezing in isopentane, tissue was coronal sectioned (10 µm thickness) with a Leica CM1900 cryostat. All sections were allowed to air dry at room temperature for 3 h and stored at −80 °C prior to immunohistology.Ethics

The authors have complied with all relevant ethical regulations. Euthanasia of T. guttata and L. oryzivora was approved by the Health Products Regulatory Authority of Ireland via authorisation AE19130-IO87 (for T. guttata) and CRN 7023925 (for L. oryzivora).Electron microscopy

Samples of soft tissues were removed from fossil specimens with sterile tools, placed on carbon tape on aluminium stubs, sputter coated with C or Au and examined using a Hitachi S3500-N and a FEI Quanta 650 FEG SEM at accelerating voltages of 5–20 kV.Untreated feathers and fixed and dehydrated samples of skin from modern birds were placed on carbon tape on aluminium stubs, sputter coated with C or Au and examined using a Hitachi S3500-N and a FEI Quanta 650 FEG SEM at accelerating voltages of 5–20 kV. Selected histological sections of L. oryzivora were deparaffinized in xylene vapour for 3 × 5 min, sputter coated with Au, and examined using a FEI Quanta 650 FEG SEM at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. The brightness and contrast of some digital images were adjusted using Deneba Canvas software.

Focussed ion beam-scanning electron microscopy

Selected samples of fossil tissue were analysed using an FEI Quanta 200 3D FIB-SEM. Regions of interest were coated with Pt using an in situ gas injection system and then milled using Ga ions at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV and a beam current of 20 nA–500 pA.Immunohistology

Histological sections were incubated in permeabilization solution (0.2% Triton X-100 in 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) for 30 min at room temperature, washed once in 10 mM PBS and blocked in 5% normal goat serum in 10 mM PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were incubated in primary antibody to cytokeratin (1:300; ThermoFisher) in 2% normal goat serum in 10 mM PBS overnight at 4 °C. Following. 3 × 5 min wash in 10 mM PBS, sections were incubated with a green fluorophore-labelled secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen) for 2 h at room temperature. After a 3 × 10 min wash in 10 mM PBS, sections were incubated in BisBenzimide nuclear counterstain (1:3000; Sigma-Aldrich) for 4 min at room temperature. Sections were washed briefly, mounted and coverslipped with PVA-DABCO.Confocal microscopy

Digital images were obtained using an Olympus AX70 Provis upright fluorescence microscope and a ×100 objective and stacked using Helicon Focus software (www.heliconfocus.com).Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be downloaded from the CORA repository (www.cora.ucc) at http://hdl.handle.net/10468/5795.Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sawyer, R. H., Knapp, L. W. & O’Guin, W. M. in Biology of the Integument 2: Vertebrates (eds Bereiter-Hahn, J. B. & Matoltsy, A. G.) 194–238 (Springer, Heidelberg, 1986).

Landmann, L. in Biology of the Integument 2: Vertebrates (eds Bereiter-Hahn, J. B. & Matoltsy, A. G.) 153–187 (Springer, New York, 1986).

Menon, G. K., Bown, B. E. & Elias, P. M. Avian epidermal differentiation: role of lipids in permeability barrier formation. Tissue Cell 18, 71–82 (1986).

Prum, R. O. & Brush, A. H. The evolutionary origin and diversification of feathers. Quart. Rev. Biol. 77, 261–295 (2002).

Xu, X., Zheng, F. & You, H. Exceptional dinosaur fossils show ontogenetic development of early feathers. Nature 464, 1338–1341 (2010).

Norell, M. A. & Xu, X. Feathered dinosaurs. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 33, 277–299 (2005).

Godefroit, P. et al.. Jurassic ornithischian dinosaur from Siberia with both feathers and scales. Science 345, 451–455 (2014).

Alibardi, L. & Gill, B. J. Epidermal differentiation in embryos of the tuatara Sphenodon punctatus (Reptilia, Sphenodontidae) in comparison with the epidermis of other reptiles. J. Anat. 211, 92–103 (2007).

Wu, P. et al. Evo-devo of amniote integuments and appendages. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 48, 249–270 (2004).

Martill, D. M., Batten, D. J. & Loydell, D. K.. new specimen of the dinosaur cf. Scelidosaurus with soft tissue preservation. Palaeontology 43, 549–559 (2000).

Lingham-Soliar, T. & Plodowski, G. in The integument of Psittacosaurus from Liaoning Province, China: taphonomy, epidermal patterns and color of. ceratopsian dinosaur. Naturwissenschaften 97, 479–486 (2010).

Martill, D. M. Organically preserved dinosaur skin: taphonomic and biological implications. Mod. Geol. 16, 61–68 (1991).

Manning,

P. L. et al. Mineralized soft-tissue structure and chemistry in.

mummified hadrosaur from the Hell Creek Formation, North Dakota (USA). Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 3429–3437 (2009).

Schweitzer, M. H. Soft tissue preservation in terrestrial Mesozoic vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 39, 187–216 (2011).

Chiappe, L. M. et al. Sauropod dinosaur embryos from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. Nature 396, 258–260 (1998).

McNamara, M. E. et al. Reconstructing carotenoid-based and structural coloration in fossil skin. Curr. Biol. 26, 1075–1082 (2016).

Navalón,

G., Marugán-Lobón, J., Chiappe, L. M., Sanz, J. L. & Buscalioni, A.

D. Soft-tissue and dermal arrangement in the wing of an Early

Cretaceous bird: implications for the evolution of avian flight. Sci. Rep. 5, 14864 (2015).

Lucas, A. M. & Stettenheim, P. R. Avian Anatomy: Integument (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, 1972).

Menon, G. K. & Menon, J. Avian epidermal lipids: functional considerations and relationship to feathering. Am. Zool. 40, 540–552 (2000).

Alibardi, L. Adaptation to the land: the skin of reptiles in comparison to that of amphibians and endotherm amniotes. J. Exp. Zool. 298B, 12–41 (2003).

Ramms, L. Keratins as the main component for the mechanical integrity of keratinocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 18513–18518 (2013).

Ishida,

A. et al. Sequential reorganization of cornifed cell keratin filaments

involving filaggrin-mediated compaction and keratin deimination. J. Invest. Dermatol. 118, 282–287 (2002).

Skerrow, D. in Biology of the Integument 2: Vertebrates (eds Bereiter-Hahn, J. B. & Matoltsy, A. G.) (Springer, Heidelberg, 1986).

Mihara,

M. Scanning electron microscopy of skin surface and the internal

structure of corneocyte in normal human skin. An application of the

osmium-dimethyl sulfoxide-osmium method. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 280, 293–299 (1988).

Sagemann,

J., Bale, D. J., Briggs, D. E. G. & Parkes, R. J. Controls on the

formation of authigenic minerals in association with decaying organic

matter: an experimental approach. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta 68, 1083–1095 (1999).

Wilby, P. R. & Briggs, D. E. G. Taxonomic trends in the resolution of detail preserved in fossil phosphatized soft tissues. Geobios 20, 493–502 (1997).

Butterfield, N. J. Leanchoilia guts and the interpretation of three-dimensional structures in Burgess Shale-type fossils. Paleobiology 28, 155–171 (2002).

McNamara,

M. E. et al. Soft-tissue preservation in Miocene frogs from Libros,

Spain: insights into the genesis of decay microenvironments. Palaios 24, 104–117 (2009).

Farage, M. A., Miller, K. W. & Maibach, H. I. Textbook of Aging Skin (Heidelberg, Springer, 2010).

Alibardi,

L. Immunocytochemical and autoradiographic studies on the process of

keratinization in avian epidermis suggests absence of keratohyalin. J. Morphol. 259, 238–253 (2004).

Alibardi,

L. & Toni, M. Cytochemical, biochemical and molecular aspects of

the process of keratinization in the epidermis of reptilian scales. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 40, 73–134 (2006).

Fukuyama, K. & Epstein, W. L. Protein synthesis studied by autoradiography in the epidermis of different species. Am. J. Anat. 122, 269–273 (1968).

Candi, E., Schmidt, R. & Melino, G. The cornified envelope:. model of cell death in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 328–340 (2005).

van

der Reest, A. J., Wolfe, A. P. & Currie, P. J. Reply to comment on:

“a densely feathered ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the

Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada. Cret. Res. 58, 108–117 (2016).

Parakkal, P. F. & Alexander, N. J. Keratinization:. Survey of Vertebrate Epithelia. (Academic Press, New York, 2012).

Markova, N. G. et al. Profilaggrin is. major epidermal calcium-binding protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 613–625 (1993).

Schachner, L. A. & Hansen, R. C. Pediatric Dermatology (Elsevier, Mosby, 2011).

Eurell, J. A. & Frappier, B. L. Textbook of Veterinary Histology (Blackwell, Oxford, 2013).

Stettenheim, P. in Avian Biology (eds Farner, D. S. & King, J. R.) 2–63 (Acadmic Press, New York, 1972).

Poinar, G. P. Jr & Poinar, R. What Bugged the Dinosaurs? Insects, Disease and Death in the Cretaceous (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2008).

Shankar, P. G. & Whitaker, N. Ecdysis in the king cobra. Russ. J. Herpet. 16, 1–5 (2009).

Alibardi,

L. & Toni, M. Characterization of keratins and associated proteins

involved in the corneification of crocodilian epidermis. Tissues Cell 39, 311–323 (2007).

Maderson,

P. F. A. & Alibardi, L. The development of the sauropsid

integument:. contribution to the problem of the origin and evolution of

feathers. Am. Zool. 40, 513–529 (2000).

Rauhut,

O. W. M., Foth, C., Tischlinger, H. & Norell, M. A. Exceptionally

preserved juvenile megalosauroid theropod dinosaur with filamentous

integument from the Late Jurassic of Germany. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11746–11751 (2012).

Porter, R. M. & Lane, E. B. Phenotypes, genotypes and their contribution to understanding keratin function. Trends Genet. 19, 278–285 (2003).

Menon,

G. K. et al. Ultrastructural organization of avian stratum corneum

lipids as the basis for facultative cutaneous waterproofing. J. Morphol. 227, 1–13 (1996).

Xu, X. et al. An integrative approach to understanding bird origins. Science 346, 153293–153210 (2014).

Nudds, R. L. & Dyke, G. J. Narrow primary feather rachises in Confuciusornis and Archaeopteryx suggest poor flight ability. Science 328, 887–889 (2010).

Dyke, G. J., de Kat, R., Palmer, C., van der Kindere, J. & Naish, B. Aerodynamic performance of the feathered dinosaur Microraptor and the evolution of feathered flight. Nat. Commun. 4, 2489 (2013).

Falk,

A. R., Kaye, T. G., Zhou, Z. & Burnham, D. A. Laser fluorescence

illuminates the soft tissue and life habits of the Early Cretaceous bird

Confuciusornis. PLoS ONE 11, e0167284 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We

thank Zheng Fang, Laura and Jonathan Kaye, Vince Lodge, Giliane Odin

and Luke Harman for assistance. Funded by a European Research Council

Starting Grant (ERC-2014-StG-637691-ANICOLEVO) and Marie Curie Career

Integration Grant (FP7-2012-CIG-618598) to M.E.M., Natural Environment

Research Council Grants (NE/E011055/1 and 1027630/1) to M.J.B. and S.K.

and by grants from the Royal Society (H.C. Wong Postdoctoral

Fellowship), National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (41125008 and

41688103), Chinese Academy of Sciences (KZCX2-EW-105) and Linyi

University to F.Z. and X.X.

Author information

Affiliations

School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University College Cork, North Mall, Cork, T23 TK30, Ireland

- Maria E. McNamara

- & Chris S. Rogers

Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Shuangling Road, Linyi City, Shandong, 276005, China

- Fucheng Zhang

School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Queen’s Road, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK

- Stuart L. Kearns

- & Michael J. Benton

UCD School of Earth Sciences, University College Dublin, Dublin, D04 N2E5, Ireland

- Patrick J. Orr

Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, University College Cork, Western Road, Cork, T12 XF62, Ireland

- André Toulouse

- & Tara Foley

School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Rd., London, E1 4NS, UK

- David W. E. Hone

School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK

- Diane Johnson

Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, 142 Xizhimenwai St., 100044, Beijing, China

- Xing Xu

- & Zhonghe Zhou

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.