Here's Why There Are No Monkeys Native to North America

Damn.

North America has its fair share of awesome creatures roaming around, but there’s one group of animals that never took root: monkeys. There are a few wild monkeys in Mexico, but in the US and Canada? None.

And when you think about it, that doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense, because there are monkeys thriving in vastly different environments all over the world. In Japan, snow monkeys love the chill of mountain air, while howler monkeys love the hot and humid climate of the Amazon rainforest. So, if monkeys can exist in all kinds of climates, why not North America?

Before we dive into that question, we need to first discuss a time period known as the Eocene Epoch, which – based on the fossil record – researchers think stretched from 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

During this time, greenhouse gases trapped inside Earth’s atmosphere caused a heat wave of epic proportions that allowed tropical rainforests to cover the globe - researchers have even found evidence that palm trees used to flourish in places like Alaska.

All of this rampant plant growth created environments perfectly suitable for early monkey species to inhabit. In fact, back then, North America wasn’t the monkey-less landscape that it is today. Instead, the US and Canada were likely just as monkey-ridden as every other place on the planet.

In 2008, researchers from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History found the fossilised remains of a 55-million-year-old Teilhardina magnoliana – an early ancestor of today’s tarsiers – in Mississippi, which suggests that monkeys or some description were in North America before they were gone.

Teilhardina magnoliana. Image: Carnegie Museum of Natural History

So, if the Eocene was such a wondrous time for North American monkeys, what the heck happened?

Well, like all good things, the Eocene Epoch eventually had to come to an end, around 33.9 million years ago. This is when an ancient strip of land or ice called the Drake Passage, which stretched from Antarctica to South America, and provided a barrier between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, is thought to have fallen apart.

While the details are heavily debated, most scientists think that – based off element scans of fish fossils from the time – the breaking of the Drake Passage allowed the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans to mix together, causing currents to carry colder water around the globe, which caused Earth’s surface temperature to drop a considerable amount.

A little cold water might not sound so extreme, but it was enough to completely change Earth’s climate, which kicked off one of the largest mass extinction events ever - referred to as the Grande Coupure (or "great break").

Since these events have happened so long ago, researchers don't fully agree on what happened during the Grande Coupure, but many think that Earth’s shifting climate wiped out millions of different creatures across the planet.

For the species of monkeys that called North America home, this meant destruction - for them and their tropical environments. In fact, the only monkey species on Earth that survived the Grande Coupe were the ones around the Equator, which, in the Western Hemisphere, means South America.

These surviving monkeys are called Platyrrhines - or New World Monkeys - and they prefer a tropical climate, which is why they still thrive so well along the Equator today. This group includes species such as capuchins, marmosets, spider monkeys, and howler monkeys.

Howler monkeys, a type of New World Monkey. Image: WikiCommons

Howler monkeys, a type of New World Monkey. Image: WikiCommons

Okay, so now that we know that monkeys actually did call North America home for millions of years before getting wiped out, thanks to a dramatic climate shift that made the world a much cooler place. One question remains unanswered: if South America was so chock-full of monkeys, why didn’t they ever migrate north again? After all, the US has forests and hot areas, too.

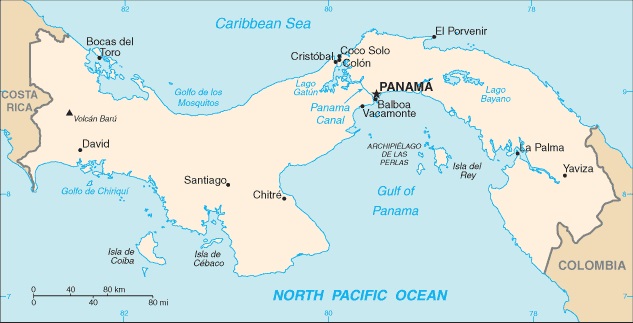

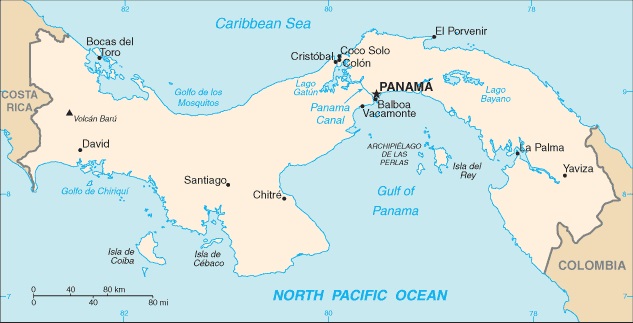

There’s actually a really easy solution to this problem: they simply couldn’t get here. Until about 3.5 million years ago - when the Isthmus of Panama formed - North and South America were separated by oceans. Still, 3 million years seems like enough time for a species to move at least a bit more north, right?

This is where adaptability comes in. Even though the Isthmus of Panama made it technically possible for monkeys to move into the US, they didn’t because they had evolved over millions of years to prefer a tropical climate full of trees. Since the majority of North America doesn’t offer these conditions - or better ones - the New World Monkeys stayed put.

"The Platyrrhines, or New World monkeys are all arboreal," palaeontologists John Flynn, from the American Museum of Natural History, told Popular Science. "They live in tropical forests; they're specialised for that kind of habitat."

The Isthmus of Panama. Image: WikiCommons

The Isthmus of Panama. Image: WikiCommons

That’s not to say that some didn’t give it a shot. Earlier this year, researchers found teeth from a 21-million-year-old monkey in rock formations near the Panama Canal. Since that's before the Isthmus of Panama formed, the researchers suggest that monkeys may have floated to North America on rafts of vegetation.

Even so, after they got to North America, they would need to have travelled through some rather barren parts of Mexico and the US before they got to a habit like Florida or Louisiana that would be remotely close to their tropical havens. While it's unknown what happened to these early, pioneering monkey populations, we can assume they eventually died out due to small population numbers.

So why would monkeys bother venturing north in the first place? Researchers suspect that the monkeys that rafted over 21 million years ago didn’t leave their South American homes in search of greener pastures, but may have rafted over on debris washed away with tropical storms. It was just by luck that they managed to survive the trip.

Nowadays, the only thing that could potentially send monkeys running north would be another dramatic climate shift that would either create a lush environment for them in North America, or destroy the areas they currently thrive in, forcing them to move or die. No one can predict if that will ever happen, but it’s a possibility, especially since climate change is already causing us humans to relocate. If it doesn't change, though, the furthest north monkeys will get is southern Mexico and Central America.

Until then, the US and Canada remain pretty much monkey-less outside of zoos. But we should never forget those ancient monkey ancestors that happened to wonder over the Isthmus of Panama, cross through Central America, take a look around at the continent, shake their heads, and wander straight back.

And when you think about it, that doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense, because there are monkeys thriving in vastly different environments all over the world. In Japan, snow monkeys love the chill of mountain air, while howler monkeys love the hot and humid climate of the Amazon rainforest. So, if monkeys can exist in all kinds of climates, why not North America?

Before we dive into that question, we need to first discuss a time period known as the Eocene Epoch, which – based on the fossil record – researchers think stretched from 56 to 33.9 million years ago.

During this time, greenhouse gases trapped inside Earth’s atmosphere caused a heat wave of epic proportions that allowed tropical rainforests to cover the globe - researchers have even found evidence that palm trees used to flourish in places like Alaska.

All of this rampant plant growth created environments perfectly suitable for early monkey species to inhabit. In fact, back then, North America wasn’t the monkey-less landscape that it is today. Instead, the US and Canada were likely just as monkey-ridden as every other place on the planet.

In 2008, researchers from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History found the fossilised remains of a 55-million-year-old Teilhardina magnoliana – an early ancestor of today’s tarsiers – in Mississippi, which suggests that monkeys or some description were in North America before they were gone.

Teilhardina magnoliana. Image: Carnegie Museum of Natural History

So, if the Eocene was such a wondrous time for North American monkeys, what the heck happened?

Well, like all good things, the Eocene Epoch eventually had to come to an end, around 33.9 million years ago. This is when an ancient strip of land or ice called the Drake Passage, which stretched from Antarctica to South America, and provided a barrier between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, is thought to have fallen apart.

While the details are heavily debated, most scientists think that – based off element scans of fish fossils from the time – the breaking of the Drake Passage allowed the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans to mix together, causing currents to carry colder water around the globe, which caused Earth’s surface temperature to drop a considerable amount.

A little cold water might not sound so extreme, but it was enough to completely change Earth’s climate, which kicked off one of the largest mass extinction events ever - referred to as the Grande Coupure (or "great break").

Since these events have happened so long ago, researchers don't fully agree on what happened during the Grande Coupure, but many think that Earth’s shifting climate wiped out millions of different creatures across the planet.

For the species of monkeys that called North America home, this meant destruction - for them and their tropical environments. In fact, the only monkey species on Earth that survived the Grande Coupe were the ones around the Equator, which, in the Western Hemisphere, means South America.

These surviving monkeys are called Platyrrhines - or New World Monkeys - and they prefer a tropical climate, which is why they still thrive so well along the Equator today. This group includes species such as capuchins, marmosets, spider monkeys, and howler monkeys.

Howler monkeys, a type of New World Monkey. Image: WikiCommons

Howler monkeys, a type of New World Monkey. Image: WikiCommonsOkay, so now that we know that monkeys actually did call North America home for millions of years before getting wiped out, thanks to a dramatic climate shift that made the world a much cooler place. One question remains unanswered: if South America was so chock-full of monkeys, why didn’t they ever migrate north again? After all, the US has forests and hot areas, too.

There’s actually a really easy solution to this problem: they simply couldn’t get here. Until about 3.5 million years ago - when the Isthmus of Panama formed - North and South America were separated by oceans. Still, 3 million years seems like enough time for a species to move at least a bit more north, right?

This is where adaptability comes in. Even though the Isthmus of Panama made it technically possible for monkeys to move into the US, they didn’t because they had evolved over millions of years to prefer a tropical climate full of trees. Since the majority of North America doesn’t offer these conditions - or better ones - the New World Monkeys stayed put.

"The Platyrrhines, or New World monkeys are all arboreal," palaeontologists John Flynn, from the American Museum of Natural History, told Popular Science. "They live in tropical forests; they're specialised for that kind of habitat."

The Isthmus of Panama. Image: WikiCommons

The Isthmus of Panama. Image: WikiCommonsThat’s not to say that some didn’t give it a shot. Earlier this year, researchers found teeth from a 21-million-year-old monkey in rock formations near the Panama Canal. Since that's before the Isthmus of Panama formed, the researchers suggest that monkeys may have floated to North America on rafts of vegetation.

Even so, after they got to North America, they would need to have travelled through some rather barren parts of Mexico and the US before they got to a habit like Florida or Louisiana that would be remotely close to their tropical havens. While it's unknown what happened to these early, pioneering monkey populations, we can assume they eventually died out due to small population numbers.

So why would monkeys bother venturing north in the first place? Researchers suspect that the monkeys that rafted over 21 million years ago didn’t leave their South American homes in search of greener pastures, but may have rafted over on debris washed away with tropical storms. It was just by luck that they managed to survive the trip.

Nowadays, the only thing that could potentially send monkeys running north would be another dramatic climate shift that would either create a lush environment for them in North America, or destroy the areas they currently thrive in, forcing them to move or die. No one can predict if that will ever happen, but it’s a possibility, especially since climate change is already causing us humans to relocate. If it doesn't change, though, the furthest north monkeys will get is southern Mexico and Central America.

Until then, the US and Canada remain pretty much monkey-less outside of zoos. But we should never forget those ancient monkey ancestors that happened to wonder over the Isthmus of Panama, cross through Central America, take a look around at the continent, shake their heads, and wander straight back.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.