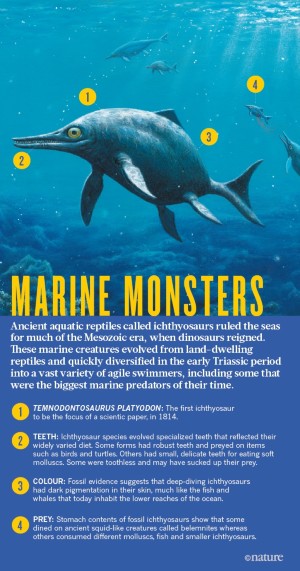

How giant marine reptiles terrorized the ancient seas

Ichthyosaurs

were some of the largest and most mysterious predators to ever prowl

the oceans. Now they are giving up their secrets.

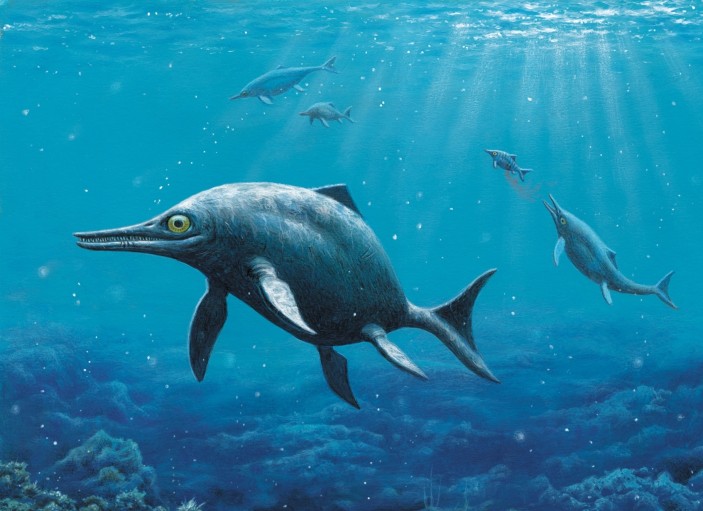

At roughly 9 metres long, Temnodontosaurus platyodon was a giant apex predator from the early Jurassic period.

Credit: Illustration by Esther Van Hulsen

Valentin

Fischer had always wanted to study fossils, perhaps dinosaurs or

extinct mammals. Instead, when he was in graduate school, Fischer ended

up sorting through a pile of bones belonging to ancient marine reptiles

known as ichthyosaurs — a group that had been mostly ignored by modern

palaeontologists. It was not exactly his dream job.

“I said, ‘Ohhh, ichthyosaurs, so boring’,” recalls Fischer. “They all look the same. It’s always a pointy snout and big eyes.”

Fischer

put his feelings aside and dutifully began combing through the fossils

stored in a research centre in provincial France. Among the specimens

stashed in plastic boxes was an ichthyosaur skull that had been

partially destroyed by ants and tree roots while buried underground.

When Fischer cleaned up the skull, he realized that it was probably a

species new to science.

As

discoveries started to pile up, he got hooked. Fischer, now at the

University of Liège, Belgium, and his colleagues have since described

seven surprising new ichthyosaurs, ranging from a tuna-sized reptile

with thin, sharp teeth1 to an animal as big as a killer whale, with a beak like that of a swordfish2.

Fischer

is part of an ichthyosaur renaissance that is sweeping palaeontology.

After ignoring them for decades, more and more researchers have started

to focus on the reptiles, which were among the top predators in the seas

for some 150 million years during the days of the dinosaurs.

Many ichthyosaurs had sharp conical teeth to help them catch fast-moving prey.

Credit: Sinclair Stammers/SPL/Getty

And that

renewed interest has brought a slew of discoveries. In the two centuries

leading up to 2000, researchers identified roughly 80 species of

ichthyosaur and close relatives. In the past 17 years, they’ve added

another 20–30, says vertebrate palaeontologist Ryosuke Motani of the

University of California, Davis, and the number of papers on the animals

has soared.

“There

are more people working on ichthyosaurs right now than I have seen for

my entire career,” says Judy Massare of the State University of New York

College at Brockport, who began studying the animals in the 1980s.

The

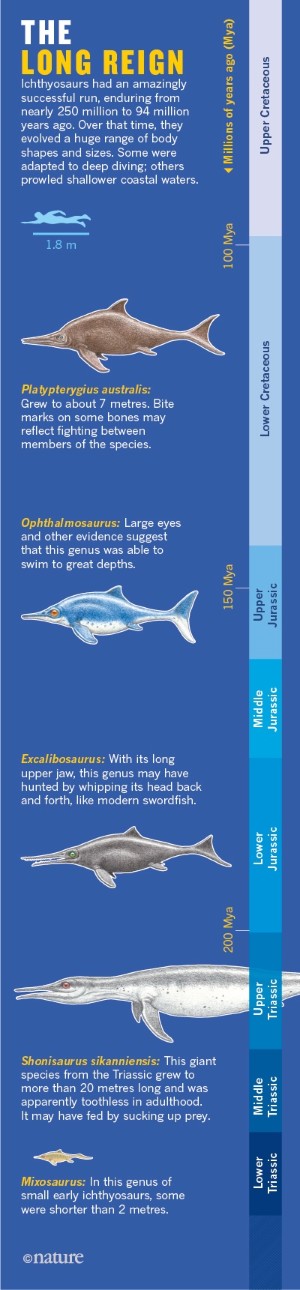

swell of research is starting to answer key questions about

ichthyosaurs, such as how and where they originated and how quickly they

came to rule the oceans. The group was even more diverse than once

thought, ranging from early near-shore creatures that undulated like

eels to giants that cruised the open ocean by swishing their powerful

tails. “They could go anywhere, just like whales,” Motani says. The

biggest ones rivalled blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) in length and were the largest predators in the Triassic seas.

The

work is also revealing the last chapters of the ichthyosaur story,

which culminated with the animals’ extinction during the Upper

Cretaceous, some 30 million years before dinosaurs disappeared. Some

scholars now argue that the ‘fish-lizards’ were vanquished in part by

the era’s drastic environmental shifts. That’s a form of redemption for

ichthyosaurs; an old theory had suggested that they vanished when more

capable predators, such as swift sharks, emerged and eclipsed them.

And

palaeontologists point to one more reason to focus on ichthyosaurs:

because their distant ancestors were land reptiles, the creatures offer a

particularly dramatic example of one of the biggest evolutionary

makeovers evident in the fossil record, says vertebrate palaeontologist

Stephen Brusatte of the University of Edinburgh, UK. “They totally

changed their bodies, biologies and behaviours in order to live in the

water.”

Fishy start

The

word ‘dinosaur’ hadn’t even been coined when a weird skeleton appeared

along the southwestern English coast in the early nineteenth century.

The bones caught the eyes of celebrated fossil hunter Mary Anning, then

no older than 13, and her brother. Their fossil fetched them £23, a

substantial sum at the time, and inspired the first scientific paper3

devoted to ichthyosaurs. The paper, published by British surgeon

Everard Home in 1814, erroneously called the animal a “fish … not of the

family of sharks or rays”. Other naturalists soon recognized the

fossils as reptiles.

Like many later ichthyosaurs, Stenopterygius quadriscissus lived in the open ocean. Black marks around fossil show the outline of the preserved skin.

Credit: Field Museum Library/Getty

The leading

lights of natural history marvelled at these creatures. Frenchman

Georges Cuvier, considered the father of vertebrate palaeontology,

called them “incredible”, and held up ichthyosaurs as support for his

theory that catastrophic mass extinctions have plagued Earth. British

geologist Charles Lyell, meanwhile, suggested that ichthyosaurs could

reappear when Earth’s climate cycled through a favourable phase.

Then

came the discovery of monstrous land animals, many of which were armed

with rows of fierce teeth. This group, named dinosaurs, captivated the

public and scientists alike. According to Fischer, they “kicked

ichthyosaurs off the pedestal of glory”. The fossils of the marine

reptiles piled up unstudied in museums, and their life story was left

incomplete.

Today’s

renaissance in ichthyosaur research is filling in the gaps, especially

the fish-lizards’ origins. It took massive anatomical change to mould

fully aquatic animals out of land reptiles. Their arms shrank and their

hands enlarged, forming seaworthy flippers. They developed the ability

to hold their breath for long stretches, even up to 20 minutes. Many

evolved huge eyes — larger than footballs, in one species — for peering

through the dark depths.

Researchers

suspect that those changes took place not long before or after an

apocalyptic mass extinction that wiped out 80% of Earth’s marine species

at the end of the Permian period4. But until the past few years, they have lacked fossils to illustrate much of that transition.

One

of the early forms helping to fill in that gap is an animal that Motani

calls “the most bizarre” early ichthyosaur ever seen, which he and his

colleagues discovered in a Chinese limestone quarry5. It had a head the size of an orange and a torso encased by wide slabs of bone, earning it the scientific name Sclerocormus parviceps,

or ‘stiff-trunk small-skull’. It dates to 248 million years ago, only 4

million years after the end-Permian extinction. A nearby quarry yielded

a snub-nosed fish-lizard of roughly the same age, Cartorhynchus lenticarpus6. About as long as a rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss),

this primitive ichthyosaur may have heaved itself around on land atop

its big flippers in much the same way that sea turtles do.

Credit: Illustration by Esther Van Hulsen

These early

animals weren’t direct ancestors of the fish-shaped ichthyosaurs. But

they are still “a big step forward in understanding where ichthyosaurs

came from”, says Erin Maxwell, a palaeontologist at the Stuttgart State

Museum of Natural History in Germany. The fossils show, for example,

that ichthyosaurs originated in what is now the eastern part of south

China. At the time, it was one of the few places in the world where land

plants flourished. Decaying vegetation would have enriched the nearby

seas, Motani says, and eventually, “seafood looked attractive to animals

that happened to live near the coastline”.

The land-worthy flippers of Cartorhynchus led

Motani to argue that it had recent ancestors that were terrestrial, or

at least amphibious. That would make it a close relative of the

land-based or amphibious ancestor of all ichthyosaurs. He interprets the

heavy bones of both Sclerocormus and Cartorhynchus as

evidence of a bottom-dwelling lifestyle. Other animals that moved from

land to sea also went through a bottom-dwelling phase, Motani says, and

with his new finds, “we have proof that ichthyosaurs went through that

heavy stage, and were most likely bottom feeders” — unlike the later

ichthyosaurs, which were creatures of the open ocean.

Other

researchers agree that the Chinese fossils provide a valuable window

into the transformation from landlubber to sea creature. The discoveries

are “some of the most interesting reptile fossils that have been found

recently”, Brusatte says. “They are giving us a glimpse of what it

actually took to turn a land-living reptile into something semi-aquatic

and then something that looked like a fish.”

Proper

ichthyosaurs, which boast long snouts and kinked tails to distinguish

them from their primitive forebears, appeared during the early Triassic

and quickly took over their new environment. Discoveries over the past

few years have revealed the wide variety of fish-lizards that emerged at

the same time as Cartorhynchus or soon after.

Credit: Adapted from Ryosuke Motani.

Take the killer-whale-sized Thalattoarchon saurophagis, or ‘lizard-eating ruler of the seas’, which was spotted in Nevada 20 years ago but not fully excavated7

until 2008. Its sharp teeth reveal it as a “large meat-eater or

flesh-tearer” that preyed on fish and other ichthyosaurs, says

vertebrate palaeontologist Martin Sander of the University of Bonn in

Germany and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, who helped

to describe the animal. During its reign in the early Middle Triassic,

only 8 million years after the end-Permian extinction, it “basically ate

anything it wanted to”, Sander says.

On

Norway’s Spitsbergen Island north of the Arctic Circle, researchers

have hacked away the permafrost to reveal large, primitive ichthyosaurs

that seem to date to the very early Triassic. The finds have yet to be

identified, but they help to show that “once these things hit the water,

they just went nuts”, says Patrick Druckenmiller, a palaeontologist at

the University of Alaska Fairbanks and part of the Spitsbergen team. The

presence of large predators at this time suggests that creatures of all

sizes and lifestyles restocked the oceans after the devastation of the

end-Permian extinction.

After

their initial burst of evolution, ichthyosaurs went through some tough

times. In the later Triassic, many species died out during one or more

mass extinctions that also claimed large fractions of species on land

and in the oceans.

After

this, the ichthyosaur’s story gets complicated. Palaeontologists had

long thought that the group was hit by a major loss of biodiversity in

the Jurassic and never really recovered. The fossil record suggested

that only a handful of species, all similar in appearance and lifestyle,

limped across the Jurassic–Cretaceous boundary 145 million years ago.

Then the whole group went extinct midway through the Cretaceous, while

dinosaurs thrived for another 30 million years or so, until an asteroid

strike wiped them out. The lack of diversity among ichthyosaur species

could have hampered their ability to compete against sharks and other

emerging predators in the seas.

Credit: Swimming styles adapted from Ryosuke Motani.

But finds

in the past few years have called that whole story into question. New

fossil discoveries show that many more species thrived during the

Cretaceous than previously recognized. These species also had more

diverse body types and food sources than researchers thought.

Ichthyosaurs’

reputation has risen in good part because of Fischer’s work — not at

sweaty dig sites but in hushed museums. “I am very bad at finding

fossils in the field,” Fischer confesses. “The only ichthyosaur I’ve

found, ever, is a single vertebra.” But the hundreds of museum specimens

that he has scrutinized — some of them left unexamined for a century —

have yielded a bounty of Cretaceous novelties. In just over a decade,

Fischer’s team and other groups have reported at least nine new species

from this period.

Fischer

and his colleagues estimate that the number of known ichthyosaur

species was just as high during parts of the early Cretaceous as during

spans of the Jurassic. It turns out that the fish-shaped reptiles called

parvipelvians, the only group of ichthyosaurs to endure from the

Triassic into the Cretaceous, had a greater range of shapes during the

middle of the early Cretaceous than at any other time in their history8.

“The diversity of ichthyosaurs in the Cretaceous, in particular, is

even higher than we ever thought it was”, says Fischer’s co-author

Darren Naish, a vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of

Southampton, UK. He calls it a “Cretaceous ichthyosaur revolution”.

Credit: ILLUSTRATIONS BY ESTHER VAN HULSEN

Then,

according to Fischer’s analysis, a one-two punch hit the ichthyosaurs. A

good number of species went extinct roughly 100 million years ago, and

the few survivors followed their relatives some 5 million to 6 million

years later. To understand why, Fischer looked to environmental factors.

He noticed a correlation between climate and extinctions: the greater

the temperature fluctuation in a given period, the more species of

ichthyosaurs winked out.

Other

scientists agree that climate disruptions could have played a big part

in the animals’ disappearance. Climate volatility “is a much better

hypothesis than any proposed so far. It matches what we know about

extinction risk in large predators today,” Maxwell says.

The

mid-Cretaceous was a difficult time in the oceans. Ichthyosaurs died

out when sea levels were high and marine oxygen levels were low. Many

other ocean groups, such as ammonites, were going downhill fast during

the same period. Ichthyosaurs, then, might be “just a small facet of

something more important”, Fischer says. He’s now looking at whether

other marine predators during the Cretaceous followed the ichthyosaur

pattern.

Fischer’s

results are not universally accepted. Motani, for example, thinks that

Fischer’s scenario is plausible, but he takes issue with the statistical

methods that Fischer uses to date ichthyosaurs’ extinction. Fischer

places the reptiles’ disappearance close to 94 million years ago, but if

the creatures went extinct at a different time, the correlation between

their fate and climate volatility would not be as strong. Fischer

stands by his conclusions, however, and says that the fossil record for

marine reptiles actually improves during the Cretaceous, which adds

confidence to conclusions about ichthyosaurs during that period.

The

debate over ichthyosaurs’ final days will continue to rage, as

scientists strive to understand the forces behind the mysterious

extinction of a successful group. Researchers also hope to understand

what befell the ichthyosaurs that died out at the end of the Triassic.

More fossils would help. So would techniques that have already been

deployed to better date the sediments containing ichthyosaurs, enabling

researchers to pinpoint species’ histories with higher precision.

The

new debates and competition characterizing the field do not perturb

Motani. He has no yearning for the lonely days when he was one of so few

ichthyosaur specialists that journals struggled to peer-review his

manuscripts. On the contrary, he is glad that more scientists are

pursuing the animals he regards as “beautiful, and beautifully adapted”.

To Motani and other partisans, ichthyosaurs are finally getting the

attention they’ve long deserved.

References

- 1Fischer, V., Masure, E., Arkhangelsky, M. S. & Godefroit, P. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 31, 1010–1025 (2011).

- 2Martin, J. E., Fischer, V., Vincent, P. & Suan, G. Palaeontology 55, 995–1005 (2012).

- 3Home, E. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 104, 571–577 (1814).

- 4Stanley, S. M. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6325–E6334 (2016).

- 5Jiang, D.-Y. et al. Sci. Rep. 6, 26232 (2016).

- 6Motani, R. et al. Nature 517, 485–488 (2015).

- 7Fröbisch, N. B., Fröbisch, J., Sander, P. M., Schmitz, L. & Rieppel, O. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 1393–1397 (2013).

- 8Fischer, V., Bardet, N., Benson, R. B., Arkhangelsky, M. S. & Friedman, M. Nature Commun. 7, 10825 (2016).

Author information

Affiliations

Related links

Related links

Related links in Nature Research

Swimming dinosaur found in Morocco 2014-Sep-11Kraken versus ichthyosaur: let battle commence 2011-Oct-11

Did reptile swimmer show mother love? 2011-Aug-11

Ichthyosaurs ate turtle soup 2003-Jul-23

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.