A history of substance

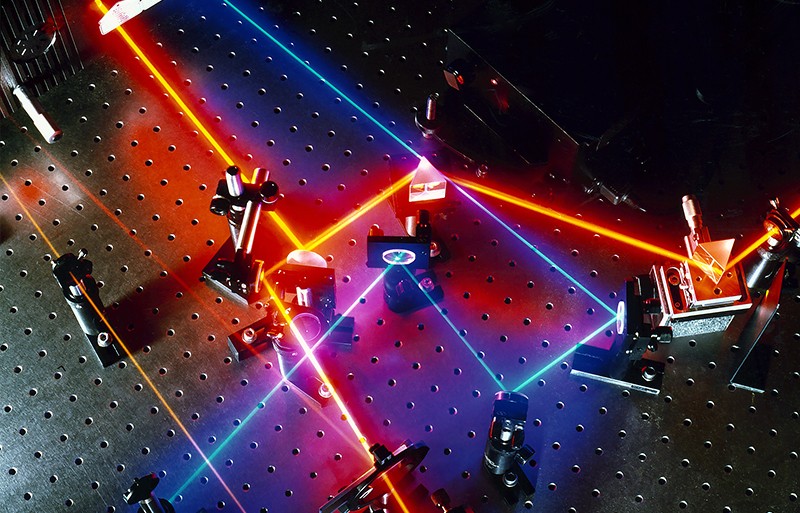

Femtosecond

laser systems, which emit ultrashort optical pulses, are used to probe

fundamental properties of solid-state materials.Credit: NREL/DOE

Studying elementary particles is not, however, what most physicists do. By almost all metrics — PhD degrees, articles in flagship journals, memberships in professional societies — the majority were not, and are not, high-energy physicists. Instead, they plough the furrows of what was once known as solid-state physics — better known since the 1970s as condensed-matter physics. This is the science that brought us superconductivity, superfluidity, magnetic memory, liquid-crystal displays and more.

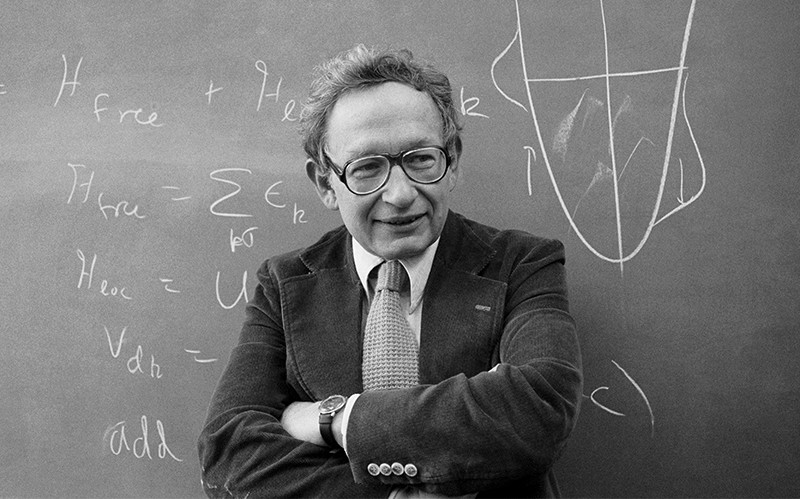

Condensed-matter physicist Philip Anderson of Bell Labs, who shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1977.Credit: Bettmann/Getty

Essa disputa era mais do que recursos. Já na década de 1970, físicos de estado sólido como Anderson e Alvin Weinberg haviam articulado uma visão alternativa da ciência da física. Os físicos de partículas justificaram-se através de um compromisso com a "ciência pura" que datava das origens da American Physical Society (APS) no final do século XIX. Como a física de alta energia sondava os menores constituintes da matéria, um reducionista diria que essa física era a mais "fundamental". Anderson discordou. Como Martin explica em um excelente capítulo, para Anderson, “física fundamental” era sobre ferromagnetos, bem como sobre quarks.

Then came the SSC. “The original Star Wars trilogy tells the story of a ragtag band of misfits, many of whom are adept at manipulating a force pervading in everyday matter, who ally to mount an insurrection against the established order and help destroy a giant, partially built beam machine,” writes Martin. The trajectory of US solid-state physics, he notes, “followed much the same plot”. Although he concedes that the SSC was more drastically affected by the end of the cold war than by intradisciplinary critique, there is no doubt where Martin’s sympathies lie.

Solid-state

physicist Alvin Weinberg (left), director of the Oak Ridge National

Laboratory in Tennessee, talking to Senator John F. Kennedy in 1959.Credit: Ed Westcott/DOE

This organizational innovation was achieved only after substantial resistance from some APS stalwarts, who perceived the purity of their ranks as becoming sullied by industrial scientists. The stalwarts included Harvard University’s John Van Vleck, even though he had trained many of the leaders of the next generation, including Anderson. Van Vleck’s objections were littered with political language: he protested against the “Balkanization” of the APS, and he thought the solid-state division was a “new-deal-bureaucratic” scheme that ought to be resisted. The conservative Van Vleck was unhappy about the direction that the United States — and with it physics — was going.

This raises a broader point about Martin’s engaging book: the politics in it are exclusive to the profession. He keeps his gaze tightly trained on physicists as they define physics to each other. The Vietnam War (and scientific work in support of it), anti-Communism, civil rights and other political fault lines — which affected physicists no less than other citizens — are mentioned in passing, if at all. Yet they must have mattered. Physics is defined not just by what physicists decide it is, but by what the broader society will (or won’t) support. That decision is made within the halls of the APS, but also in those of Congress.

Construction of the Superconducting Super Collider, a US high-energy physics project, was cancelled by Congress in 1993.Credit: SSC Lab./SPL

doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-06696-4

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.