Neanderthal artists made oldest-known cave paintings

Neanderthals painted caves in what is now Spain before their cousins, Homo sapiens, even arrived in Europe, according to research published today in Science1.

The finding suggests that the extinct hominids, once assumed to be

intellectually inferior to humans, may have been artists with complex

beliefs.

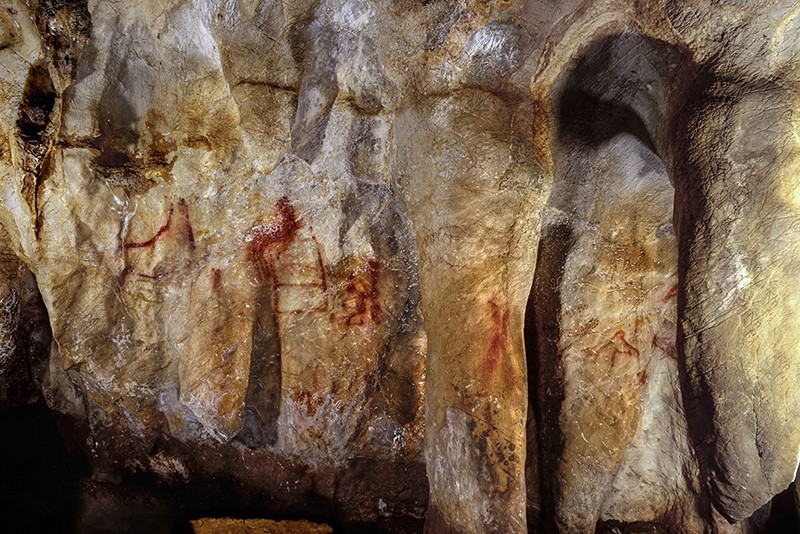

Ladder-like shapes, dots and handprints were painted and

stenciled deep in caves at three sites in Spain. Their precise meaning

may forever be unknowable, says Alistair Pike, an archaeologist at the

University of Southampton, UK, who co-authored the study, but they were

almost certainly meaningful to our lost kin. “It wasn’t simply

decorating your living space,” Pike says. “People were making journeys

into the darkness.”

Humans are thought to have arrived in Europe

from Africa around 40,000–45,000 years ago. The three caves in different

parts of Spain yielded artworks that are at least 65,000 years old,

according to uranium-thorium dating of calcium carbonate that had formed

on top of the art.

These mineral deposits develop slowly, as

water containing calcium comes into contact with cave surfaces. The

water also contains trace levels of uranium from the rock. After the

calcium carbonate has precipitated out of the water, a clock of sorts

begins to tick, as uranium decays into thorium at a steady, known rate.

A datação por urânio-tório tem sido usada na geologia há décadas, mas raramente foi empregada para estimar a idade da arte rupestre. Alguns arqueólogos são céticos quanto à abordagem. Eles sugerem que o carbonato de cálcio poderia ter se dissolvido e se cristalizou novamente depois que foi formado - um processo que também poderia ter lavado algum urânio, fazendo com que uma amostra do mineral aparecesse mais velha do que é.

Até agora, a mais antiga arte rupestre conhecida era de aproximadamente 40.000 anos

— stenciled hands and animals in an Indonesian site2 that was dated in 2014, and discs and hand stencils from a cave in Cantabria, Spain3, that were found by Pike and his colleagues in 2012.

Drawing conclusions

Anticipating

objections about its dating method, Pike’s team collected samples from

the outer, middle and inner layers of the calcium carbonate crust and

dated them separately. As they expected, the inner samples closest to

the art yielded the oldest dates, and the outer samples had younger

dates because they would have been later layers of precipitate. “We

can’t think of any processes that would re-crystalize the calcite and

still keep them in stratigraphic order,” Pike says. The researchers

waited three years to publish their results after finding their first

clearly pre-human date so they could collect multiple examples and

publish their methodology.

Some archaeologists, however, remain unconvinced. “In my

opinion, we have to be cautious with these ‘quite old’ results until we

have a much larger corpus of dating results,” says Roberto Ontañón

Peredo, an archaeologist at the Prehistory and Archaeology Museum of

Cantabria in Santander, Spain. “We have to keep a cool head.”

Pike

suggests that such reluctance to believe that Neanderthals were

creating cave art may have less to do with methodological disputes than

plain old species-ism. “People are very prejudiced against

Neanderthals,” he says.

Paola Villa, an archaeologist who studies

Neanderthal culture at the University of Colorado Boulder, says that

Neanderthals have an undeserved reputation as moronic brutes. She says

that since their bodies were “archaic” in the sense of having features

of older hominids — such as heavier bones and pronounced brow ridges —

everyone assumed they were “behaviourally archaic” as well. “They were

stereotyped as knuckle-dragging dimwits,” she says.

This

assumption has fed into theories about their extinction, which have

tended to hinge on humans outcompeting slower, dumber Neanderthals. But

Villa says a careful review of the research shows “no support for a

cognitive gap between Neanderthals and modern humans”. Newer theories

instead focus on factors such as low population density and “assimilation by interbreeding” with humans.

The

ladder-like art Pike and his colleagues ascribe to Neanderthal artists

has, inside its rectangular forms, faint paintings of animals. These

remain a mystery, but Pike speculates that they might be the result of

“modern humans coming in and adding their own art”. Humans and

Neanderthals may have thought alike, interbred and even — in a way —

collaborated artistically, he says.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.