When Trilobites Ruled the World

Image

WASHINGTON — Trilobites

may be the archetypal fossils, symbols of an archaic world long swept

beneath the ruthless road grader of time. But we should all look so

jaunty after half a billion years.

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Brian T. Huber, chairman of paleobiology, points to a flawless specimen of Walliserops, a five-inch trilobite that swam the Devonian seas

around what is now Morocco some 150 million years before the first

dinosaurs hatched. With its elongated, triple-tined head horn and a

bristle brush of spines encircling its lower body, the trilobite could

be a kitchen utensil for Salvador Dalí. Nearby is the even older Boedaspis ensifer, its festive nimbus of spiny streamers pointing every which way like the ribbons of a Chinese dancer.

In

a back room of the museum, Dr. Huber opens a drawer to reveal a dark,

mouse-size and meticulously armored trilobite that has yet to be

identified and that strains up from its sedimentary bed as though

determined to break free.

“A lot of

people, when they see these fossils, don’t believe they’re real,” said

Dr. Huber, who is 54, fit from years of fieldwork, and proud that the state fossil of his native Ohio is a trilobite. “They think they must be artists’ models.”

Advertisement

The

fossils are real, and so, too, is scientists’ unshakable passion for

trilobites (TRY-luh-bites), a diverse and illuminating group of marine

animals, distantly related to the horseshoe crab, that once dominated

their environment as much as dinosaurs and humans would later dominate

theirs — and that still have a few surprises up their jointed sleeves.

Image

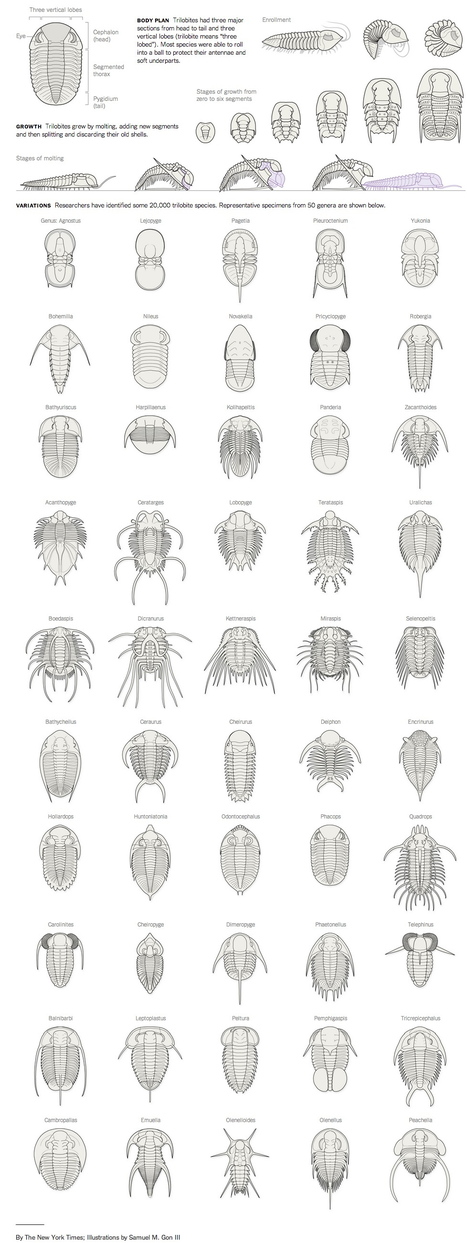

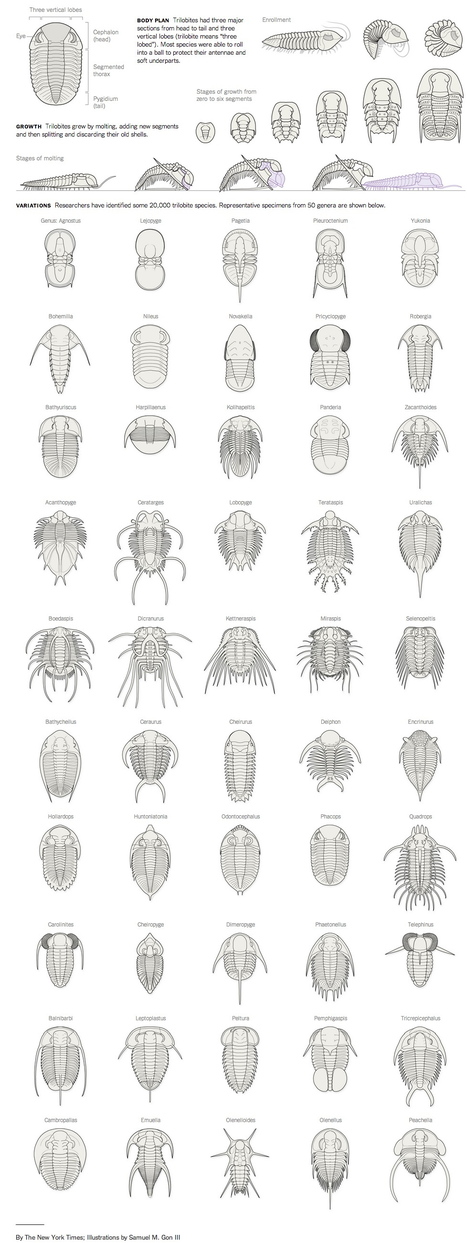

In

a series of recent reports, scientists describe fresh insights into the

trilobite’s crystal-eyed visual system, unique in the animal kingdom,

and its distinctive body plan, a hashtag of horizontal segments arrayed

along three vertical lobes that allowed the trilobite to roll up into a

defensive ball against predators and sea squalls.

Other

researchers have found evidence that some trilobites were highly

social, migrating long distances in a head-to-tail procession as they

searched for food, or gathering together during molting season at a kind

of Trilo’s Retreat, where the trilobites could simultaneously shuck off

their carapaces and seek out mates.

“It looks like a lot of trilobite mating behavior happened when they were in a soft-shelled form,” said Carlton E. Brett, a professor of geology at the University of Cincinnati, who has presented research on trilobite assemblages to the Geological Society of America and elsewhere. “They did it in the nude.”

Advertisement

To

investigate trilobite social life, Dr. Brett and his colleagues

analyzed numerous examples of mass burial sites, where congregations of

trilobites had been trapped in place by the sedimentary upheavals from

violent sea storms, just as the residents of Pompeii were smothered in midscream by Vesuvian ash.

“You

feel a little bad for the trilobites, but it’s incredible seeing these

things preserved in the act of life processes,” Dr. Brett said. “It’s

frozen behavior.”

Trilobites: Variations on a Theme

Over 300 million years, trilobites evolved a diverse and successful array of forms while maintaining a simple, common body plan.

On

a similarly erotic note, some researchers have proposed that many of

the more gothic features identified in the trilobite fossil record — the

oversized head horns, the curlicue shoulder spines, and maybe the

eyestalks that look like a couple of periscopes plunked on either side

of a trilobite’s face — are the trilobitic equivalent of a peacock’s

tail, results of sexual selection rather than adaptations to the

environment.

By this argument, the

showstoppers in a given trilobite collection are probably males, their

appurtenances having evolved to impress females or intimidate rival

males. “If you look at the diversity of life now, most of the weird,

exaggerated things we find are sexually selected,” said Robert J. Knell

of the Queen Mary University of London. “There’s no reason to think

evolution was working differently in the past.”

Dr. Knell and the renowned trilobite expert Richard A. Fortey of the Natural History Museum in London reported their ideas about sexual selection among trilobites in the journal Biology Letters.

The

sticking point: Researchers have no clue how to determine a trilobite

fossil’s sex. If a big trident marks a Walliserops as male, for example,

scientists have yet to identify who his drab peahen may have been. As

Dr. Brett said, the “X-rated parts” don’t readily fossilize.

Advertisement

By

contrast, the fossil record brims with trilobite PG-rated parts, the

mineralized remains of the hard outer sheath, or exoskeleton, that

covered much of the trilobite’s body. Not only did trilobites persist

for close to 300 million years — almost twice as long as the dinosaurs —

and thus had ample opportunity to leave heaps of their carcasses

behind, but all the molted shells they discarded while alive were

likewise fair game for stratigraphic immortality.

“Trilobites,” Dr. Fortey has written, “were veritable fossil factories.”

Researchers

particularly appreciate the trilobite’s developmental consistency, the

way it avoided any complicating, butterfly-style metamorphosis and

instead grew larger by simply generating new segments toward the rear

and then “jacking itself apart,” said Nigel Hughes,

a trilobite specialist at the University of California, Riverside.

“They changed relatively little as they went through their molts,” he

said, “so we’ve been able to assemble growth series, stage after stage,

for a number of trilobite species.”

That

accordion approach to maturation played out in a symphonic diversity of

forms. Researchers have identified some 20,000 trilobite species, which

range in adult size from a quarter-inch to the dimensions of a kitchen

tabletop. Some scurried on the sea floor or buried into the sediment and

ate detritus. Others swam or floated near the surface and may have

hunted small invertebrates.

“They

can have scoops or shovels, be fantastically spiny or beautifully

streamlined,” Dr. Hughes said. “They diverged to really explore their

evolutionary space, but they maintain that common body plan” — the three

vertical lobes, or trilobes, that give the class its name.

Researchers

were long at a loss to explain the origins of all the architectural

partitioning. They believed that early trilobites lived flatly, like

flounders, and only later would take advantage of their longitudinal

seams to begin enrolling — curling up into a ball, armadillo-style, to

protect their soft underparts.

Advertisement

But last fall a team from the University of Cambridge and the Chinese Academy of Sciences reported the discovery

of fully enrolled fossils dating to the trilobite’s advent, in the

Cambrian period roughly 510 million years ago, suggesting that the lobes

were about enrollment from the start. Later still, with the rise of

jawed fish and other fierce predators, trilobites evolved increasingly

elaborate enrollment techniques, including tips and sockets that locked

together and made the rounded trilobite almost impossible to pry apart.

Video

Scientists

can also spy the escalating threats that trilobites confronted by

studying the evolution of their eyes. Trilobite eyes were unlike those

of virtually any other known animal, the lenses built not of protein but

of calcite crystals, lending the animals a “stony stare,” as Dr. Fortey

put it.

In most trilobites, each

compound orb held hundreds of tiny calcite lenses, arranged in a

tightknit honeycomb pattern, like the eye of a fly. But fairly late in

trilobite evolution one group developed a different sort of eye,

composed of a smaller number of larger, separated calcite lenses.

As they described last spring in the journal Scientific Reports, Brigitte Schoenemann of the Universities of Cologne and Bonn in Germany and Euan N. K. Clarkson of the University of Edinburgh, used advanced scanning techniques, including synchrotron radiation,

to examine specimens of these later, larger-lensed trilobite eyes. On

the back of the lenses, the scientists were astonished to see traces of

the sensory receptor cells that once linked the eyes to the brain.

“It

was extraordinary,” Dr. Schoenemann said. “As far as we know, these are

the oldest receptor cells that have ever been seen in any fossil

animal.”

Analyzing the

microstructure of the receptor tracings, the researchers concluded that

the eyes were designed to work optimally in lowlight, murky conditions, a

sign that some trilobites were turning reclusive, descending to deeper

waters or burrowing farther into the mud to escape the proliferation of

toothy marine predators and new crustacean competitors.

Toward the end of the Paleozoic Era, the once-thriving trilobite tribe had been reduced to a scattering of species. And they, too, vanished in the great Permian extinction 252 million years ago.

Advertisement

Yet

the trilobite’s appeal is undimmed. “People always like trilobites,”

Dr. Schoenemann said. “They find them sweet.” Those big eyes. That

rounded head. Trilobites “show a scheme of childlike characteristics,”

Dr. Schoenemann added. “You want to protect them.”

Childlike, you say? Just wait till they molt.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.