Como répteis marinhos gigantes aterrorizaram os mares antigos

Volume Natureza 543 , páginas 603 - 607 ( 2017 )

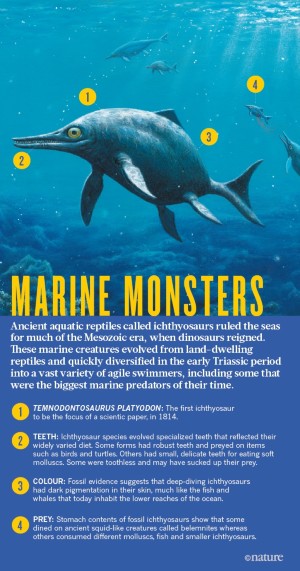

Os ictiossauros foram alguns dos maiores e mais misteriosos predadores que já rondaram os oceanos. Agora eles estão desistindo de seus segredos.

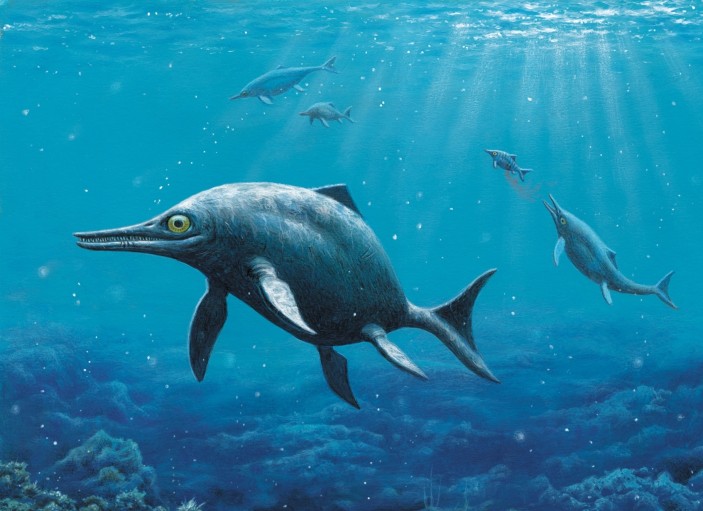

Com aproximadamente 9 metros de comprimento, o Temnodontosaurus platyodon era um predador gigante do ápice do início do período jurássico. Crédito: Ilustração de Esther Van Hulsen.

Valentin Fischer sempre quis estudar fósseis, talvez dinossauros ou mamíferos extintos.

Em vez disso, quando ele estava na faculdade, Fischer acabou examinando

uma pilha de ossos pertencentes a répteis marinhos antigos conhecidos

como ictiossauros - um grupo que havia sido quase sempre ignorado pelos

paleontologistas modernos. Não era exatamente o emprego dos seus sonhos.

"Eu disse: 'Ohhh, ictiossauros, tão chatos'", lembra Fischer. "Todos eles parecem iguais. É sempre um focinho pontudo e olhos grandes.

Fischer deixou de lado seus sentimentos e obedientemente começou a

vasculhar os fósseis armazenados em um centro de pesquisa na França

provincial.

Entre os espécimes guardados em caixas plásticas, havia um crânio de

ictiossauro que havia sido parcialmente destruído por formigas e raízes

de árvores enquanto enterrado no subsolo. Quando Fischer limpou o crânio, ele percebeu que provavelmente era uma espécie nova para a ciência.

Quando as descobertas começaram a se acumular, ele ficou viciado.

Fischer, agora na Universidade de Liège, na Bélgica, e seus colegas

descreveram sete novos ictiossauros surpreendentes, variando de um

réptil do tamanho de atum com dentes finos e afiados 1 a um animal do tamanho de uma baleia assassina, com um bico assim. de um peixe-espada 2 .

Fischer faz parte de um renascimento de ictiossauros que está varrendo a paleontologia.

Depois de ignorá-los por décadas, mais e mais pesquisadores começaram a

se concentrar nos répteis, que estavam entre os principais predadores

nos mares por cerca de 150 milhões de anos durante os dias dos

dinossauros.

Muitos ictiossauros possuíam dentes cônicos afiados para ajudá-los a capturar presas em movimento rápido. Crédito: Sinclair Stammers / SPL / Getty

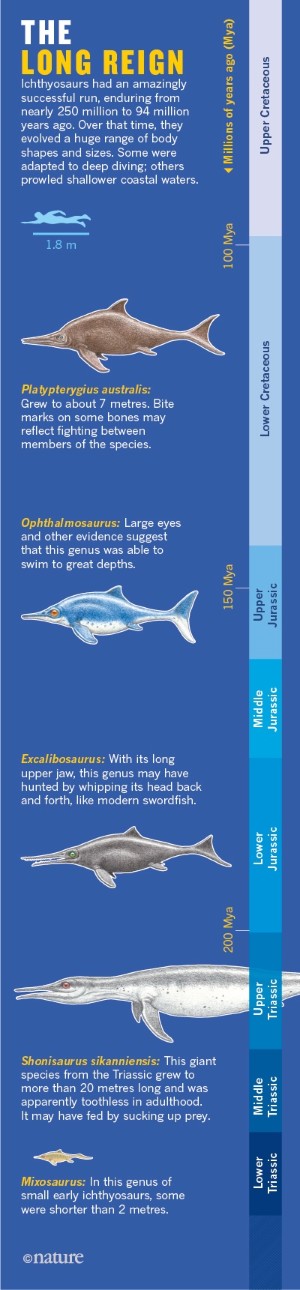

E esse interesse renovado trouxe uma série de descobertas. Nos dois séculos anteriores a 2000, os pesquisadores identificaram cerca de 80 espécies de ictiossauros e parentes próximos.

Nos últimos 17 anos, eles adicionaram outros 20 a 30, diz o

paleontólogo de vertebrados Ryosuke Motani, da Universidade da

Califórnia, Davis, e o número de artigos sobre os animais aumentou.

"Há mais pessoas trabalhando em ictiossauros agora do que eu tenho

visto em toda a minha carreira", diz Judy Massare, da Universidade

Estadual de Nova York College, em Brockport, que começou a estudar os

animais na década de 1980.

O aumento da pesquisa está começando a responder perguntas importantes

sobre os ictiossauros, como como e onde eles se originaram e a rapidez

com que chegaram a dominar os oceanos.

O grupo era ainda mais diverso do que se pensava, desde criaturas

próximas da costa que ondulavam como enguias a gigantes que cruzavam o

oceano aberto balançando suas caudas poderosas. "Eles poderiam ir a qualquer lugar, assim como as baleias", diz Motani. As maiores rivalizavam com as baleias azuis ( Balaenoptera musculus ) em comprimento e eram os maiores predadores nos mares do Triássico.

O trabalho também está revelando os últimos capítulos da história do

ictiossauro, que culminaram com a extinção dos animais durante o

Cretáceo Superior, cerca de 30 milhões de anos antes do desaparecimento

dos dinossauros.

Alguns estudiosos agora argumentam que os 'peixes-lagartos' foram

derrotados em parte pelas drásticas mudanças ambientais da época. Essa é uma forma de redenção para os ictiossauros;

uma velha teoria sugeria que eles desapareciam quando predadores mais

capazes, como os rápidos tubarões, emergiam e os eclipsavam.

E os paleontólogos apontam para mais um motivo para se concentrar nos

ictiossauros: porque seus ancestrais distantes eram répteis terrestres,

as criaturas oferecem um exemplo particularmente dramático de uma das

maiores reformas evolutivas evidentes no registro fóssil, diz o

paleontólogo vertebrado Stephen Brusatte, da Universidade de Edimburgo. ,

UK. "Eles mudaram totalmente seus corpos, biologias e comportamentos para viver na água."

Começo suspeito

A palavra dinossauro ainda não havia sido inventada quando um esqueleto

estranho apareceu ao longo da costa sudoeste do país no início do

século XIX. Os ossos chamaram a atenção da célebre caçadora de fósseis Mary Anning, então com 13 anos e seu irmão. O fóssil deles buscou 23 libras, uma quantia substancial na época, e inspirou o primeiro artigo científico 3 dedicado aos ictiossauros.

O artigo, publicado pelo cirurgião britânico Everard Home em 1814,

erroneamente chamou o animal de "peixe ... não da família de tubarões ou

raias". Outros naturalistas logo reconheceram os fósseis como répteis.

Como muitos ictiossauros posteriores, Stenopterygius quadriscissus vivia em mar aberto. Marcas pretas ao redor do fóssil mostram o contorno da pele preservada. Crédito: Field Museum Library / Getty

As principais luzes da história natural se maravilhavam com essas criaturas.

O francês Georges Cuvier, considerado o pai da paleontologia de

vertebrados, os chamou de "incríveis" e sustentou os ictiossauros como

apoio à sua teoria de que extinções em massa catastróficas atormentaram a

Terra.

Enquanto isso, o geólogo britânico Charles Lyell sugeriu que os

ictiossauros pudessem reaparecer quando o clima da Terra passasse por

uma fase favorável.

Então veio a descoberta de animais terrestres monstruosos, muitos dos quais armados com fileiras de dentes ferozes. Esse grupo, chamado dinossauros, cativou o público e os cientistas. Segundo Fischer, eles "expulsaram ictiossauros do pedestal da glória". Os fósseis dos répteis marinhos empilhados sem estudo nos museus, e sua história de vida foi deixada incompleta.

O renascimento de hoje na pesquisa de ictiossauros está preenchendo as lacunas, especialmente as origens dos lagartos-peixes. Foram necessárias grandes alterações anatômicas para moldar animais totalmente aquáticos a partir de répteis terrestres. Seus braços se encolheram e as mãos aumentaram, formando nadadeiras em condições de navegar. Eles desenvolveram a capacidade de prender a respiração por longos períodos, até 20 minutos.

Muitos desenvolveram olhos enormes - maiores que bolas de futebol, em

uma espécie - para espiar através das profundezas escuras.

Os pesquisadores suspeitam que essas mudanças tenham ocorrido pouco

antes ou depois de uma extinção em massa apocalíptica que destruiu 80%

das espécies marinhas da Terra no final do período do Permiano 4 . Mas até os últimos anos, eles careciam de fósseis para ilustrar grande parte dessa transição.

Uma das primeiras formas que ajudam a preencher essa lacuna é um animal

que Motani chama de “o mais bizarro” ictiossauro já visto, que ele e

seus colegas descobriram em uma pedreira chinesa de calcário 5 .

Tinha uma cabeça do tamanho de uma laranja e um tronco envolto por grandes placas de osso, ganhando o nome científico de Sclerocormus parviceps , ou "crânio pequeno de tronco duro". Ela data de 248 milhões de anos atrás, apenas 4 milhões de anos após a extinção final do Permiano.

Uma pedreira próxima produziu um peixe-lagarto com aproximadamente a mesma idade, Cartorhynchus lenticarpus 6 . Aproximadamente enquanto uma truta arco-íris ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ), este ictiossauro primitivo pode ter se erguido em terra sobre suas grandes nadadeiras, da mesma maneira que as tartarugas marinhas.

Tinha uma cabeça do tamanho de uma laranja e um tronco envolto por grandes placas de osso, ganhando o nome científico de Sclerocormus parviceps , ou "crânio pequeno de tronco duro". Ela data de 248 milhões de anos atrás, apenas 4 milhões de anos após a extinção final do Permiano.

Uma pedreira próxima produziu um peixe-lagarto com aproximadamente a mesma idade, Cartorhynchus lenticarpus 6 . Aproximadamente enquanto uma truta arco-íris ( Oncorhynchus mykiss ), este ictiossauro primitivo pode ter se erguido em terra sobre suas grandes nadadeiras, da mesma maneira que as tartarugas marinhas.

Crédito: Ilustração de Esther Van Hulsen

Esses animais primitivos não eram ancestrais diretos dos ictiossauros em forma de peixe.

Mas eles ainda são "um grande passo à frente para entender de onde

vieram os ictiossauros", diz Erin Maxwell, paleontologista do Museu

Estadual de História Natural de Stuttgart, na Alemanha. Os fósseis mostram, por exemplo, que os ictiossauros se originaram no que é hoje a parte oriental do sul da China. Na época, era um dos poucos lugares do mundo em que as plantas terrestres floresciam.

A vegetação em decomposição teria enriquecido os mares próximos, diz

Motani, e eventualmente "os frutos do mar pareciam atraentes para os

animais que moravam perto da costa".

As nadadeiras dignas de terra de Cartorhynchus levaram Motani a argumentar que possuía ancestrais recentes que eram terrestres, ou pelo menos anfíbios. Isso o tornaria um parente próximo do ancestral terrestre ou anfíbio de todos os ictiossauros. Ele interpreta os ossos pesados de Esclerocormus e Cartorhynchus como evidência de um estilo de vida que vive no fundo.

Outros animais que se mudaram da terra para o mar também passaram por

uma fase de moradia no fundo, diz Motani, e com suas novas descobertas,

"temos provas de que os ictiossauros passaram por esse estágio pesado e

eram provavelmente alimentadores de fundo" - ao contrário dos

ictiossauros posteriores , que eram criaturas do oceano aberto.

Outros pesquisadores concordam que os fósseis chineses fornecem uma

janela valiosa para a transformação de uma lagarta em uma criatura

marinha. As descobertas são "alguns dos fósseis de répteis mais interessantes que foram encontrados recentemente", diz Brusatte.

"Eles estão nos dando uma idéia do que foi realmente necessário para

transformar um réptil que vive em terra em algo semi-aquático e depois

algo que parecia um peixe".

Os ictiossauros adequados, que ostentam focinhos compridos e caudas

dobradas para distingui-los de seus antepassados primitivos,

apareceram durante o início do Triássico e rapidamente assumiram seu

novo ambiente. As descobertas nos últimos anos revelaram a grande variedade de lagartos-peixes que surgiram ao mesmo tempo que Cartorhynchus ou logo depois.

Crédito: Adaptado de Ryosuke Motani.

Pegue o Thalattoarchon saurophagis do

tamanho de uma baleia assassina, ou 'régua dos mares comedores de

lagartos', que foi vista em Nevada há 20 anos, mas não foi totalmente

escavada 7

até 2008. Seus dentes afiados o revelam um “grande comedor de carne ou

carnívoros ”que caçavam peixes e outros ictiossauros, diz o paleontólogo

de vertebrados Martin Sander, da Universidade de Bonn, na Alemanha, e o

Museu de História Natural do Condado de Los Angeles, que ajudou a

descrever o animal.

Durante seu reinado no início do Triássico Médio, apenas 8 milhões de

anos após a extinção do Permiano, ele “comeu basicamente o que

quisesse”, diz Sander.

Na ilha Spitsbergen, na Noruega, ao norte do Círculo Polar Ártico, os

pesquisadores cortaram o permafrost para revelar grandes ictiossauros

primitivos que parecem datam do Triássico.

As descobertas ainda precisam ser identificadas, mas ajudam a mostrar

que "quando essas coisas atingem a água, ficam loucas", diz Patrick

Druckenmiller, paleontologista da Universidade do Alasca Fairbanks e

parte da equipe de Spitsbergen.

A presença de grandes predadores neste momento sugere que criaturas de

todos os tamanhos e estilos de vida reabasteceram os oceanos após a

devastação da extinção final do Permiano.

Após sua explosão inicial de evolução, os ictiossauros passaram por momentos difíceis.

No Triássico posterior, muitas espécies morreram durante uma ou mais

extinções em massa que também reivindicaram grandes frações de espécies

na terra e nos oceanos.

Depois disso, a história do ictiossauro fica complicada.

Os paleontólogos pensavam há muito tempo que o grupo foi atingido por

uma grande perda de biodiversidade no Jurássico e nunca realmente se

recuperou.

O registro fóssil sugeria que apenas um punhado de espécies, todas

parecidas em aparência e estilo de vida, mancavam através da fronteira

jurássico-cretáceo há 145 milhões de anos.

Então todo o grupo foi extinto no meio do Cretáceo, enquanto os

dinossauros prosperaram por mais 30 milhões de anos, aproximadamente,

até que um ataque de asteróide os exterminou.

A falta de diversidade entre as espécies de ictiossauros poderia ter

prejudicado sua capacidade de competir contra tubarões e outros

predadores emergentes nos mares.

Crédito: Estilos de natação adaptados de Ryosuke Motani.

Mas descobertas nos últimos anos colocaram toda essa história em questão. Novas descobertas fósseis mostram que muito mais espécies prosperaram durante o Cretáceo do que o anteriormente reconhecido. Essas espécies também tinham mais tipos de corpos e fontes alimentares do que os pesquisadores pensavam.

A reputação dos ictiossauros aumentou em boa parte por causa do

trabalho de Fischer - não em locais de escavação suados, mas em museus

silenciosos. "Sou péssimo em encontrar fósseis no campo", confessa Fischer.

“O único ictiossauro que eu encontrei é uma única vértebra.” Mas as

centenas de espécimes de museus que ele examinou - alguns deles deixados

sem exame por um século - renderam uma abundância de novidades do

Cretáceo. Em pouco mais de uma década, a equipe de Fischer e outros grupos relataram pelo menos nove novas espécies desse período.

Fischer e seus colegas estimam que o número de espécies conhecidas de

ictiossauros era tão alto durante partes do início do Cretáceo quanto

durante períodos do Jurássico.

Acontece que os répteis em forma de peixe chamados parvipélvios, o

único grupo de ictiossauros a resistir do Triássico ao Cretáceo, tinham

uma gama maior de formas durante o meio do início do Cretáceo do que em

qualquer outro momento da história 8 .

"A diversidade de ictiossauros no Cretáceo, em particular, é ainda

maior do que se pensava", diz Darren Naish, co-autor de Fischer,

paleontologista de vertebrados da Universidade de Southampton, Reino

Unido. Ele chama isso de "revolução do ictiossauro cretáceo".

Crédito: ILUSTRAÇÕES DE ESTHER VAN HULSEN

Então, de acordo com a análise de Fischer, um soco de um a dois atingiu os ictiossauros.

Um bom número de espécies se extinguiu cerca de 100 milhões de anos

atrás, e os poucos sobreviventes seguiram seus parentes cerca de 5 a 6

milhões de anos depois. Para entender por que, Fischer olhou para fatores ambientais.

Ele notou uma correlação entre clima e extinções: quanto maior a

flutuação de temperatura em um determinado período, mais espécies de

ictiossauros desapareceram.

Outros cientistas concordam que as perturbações climáticas podem ter tido um papel importante no desaparecimento dos animais. A volatilidade climática “é uma hipótese muito melhor do que qualquer proposta até agora. Ele corresponde ao que sabemos sobre o risco de extinção em grandes predadores hoje ”, diz Maxwell.

O meio do período cretáceo foi um período difícil nos oceanos. Os ictiossauros desapareceram quando o nível do mar estava alto e o oxigênio marinho estava baixo. Muitos outros grupos oceânicos, como amonites, estavam descendo rapidamente durante o mesmo período. Os ictiossauros, então, podem ser "apenas uma pequena faceta de algo mais importante", diz Fischer. Ele agora está analisando se outros predadores marinhos durante o Cretáceo seguiram o padrão de ictiossauros.

Os resultados de Fischer não são universalmente aceitos.

Motani, por exemplo, acha que o cenário de Fischer é plausível, mas ele

discorda dos métodos estatísticos que Fischer usa para datar a extinção

dos ictiossauros.

Fischer coloca o desaparecimento dos répteis perto de 94 milhões de

anos atrás, mas se as criaturas fossem extintas em um momento diferente,

a correlação entre seu destino e a volatilidade climática não seria tão

forte.

Fischer sustenta suas conclusões, no entanto, e diz que o registro

fóssil de répteis marinhos realmente melhora durante o Cretáceo, o que

acrescenta confiança às conclusões sobre os ictiossauros durante esse

período.

O debate sobre os dias finais dos ictiossauros continuará em fúria,

enquanto os cientistas se esforçam para entender as forças por trás da

misteriosa extinção de um grupo de sucesso. Os pesquisadores também esperam entender o que aconteceu com os ictiossauros que morreram no final do Triássico. Mais fósseis ajudariam.

Assim como técnicas que já foram implantadas para datar melhor os

sedimentos contendo ictiossauros, permitindo que os pesquisadores

identifiquem a história das espécies com maior precisão.

Os novos debates e competições que caracterizam o campo não perturbam Motani.

Ele não anseia pelos dias solitários em que era um dos poucos

especialistas em ictiossauros que os jornais se esforçavam para revisar

seus manuscritos por pares.

Pelo contrário, ele está feliz que mais cientistas estejam perseguindo

os animais que ele considera "bonitos e belamente adaptados". Para Motani e outros partidários, os ictiossauros estão finalmente recebendo a atenção que merecem há muito tempo.

Referências

- 1 Fischer, V., Masure, E., Arkhangelsky, MS & Godefroit, PJ Vertebr. Paleontol. 31 , 1010-1025 (2011).

- 2 Martin, JE, Fischer, V., Vincent, P. e Suan, G. Paleontologia 55 , 995–1005 (2012).

- 3 Casa, E. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 104 , 571-577 (1814).

- 4 Stanley, SM Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. EUA 113 , E6325-E6334 (2016).

- 5 Jiang, D.-Y. et al. Sci. 6 , 26232 (2016).

- 6 Motani, R. et ai. Nature 517 , 485-488 (2015).

- 7 Fröbisch, NB, Fröbisch, J., Sander, PM, Schmitz, L. & Rieppel, O. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 1393–1397 (2013).

- 8 Fischer, V., Bardet, N., Benson, RB, Arkhangelsky, MS e Friedman, M. Nature Commun. 7 , 10825 (2016).

Informação sobre o autor

Afiliações

Links Relacionados

Links Relacionados

Links relacionados em Nature Research

Dinossauro nadador encontrado em Marrocos 2014-Sep-11Kraken versus ichthyosaur: deixe a batalha começar 2011-Oct-11

O nadador de répteis mostrou amor à mãe? 11 de agosto de 2011

Ichthyosaurs comeu sopa de tartaruga 23-Jul-23