Ardi walked the walk 4.4 million years ago

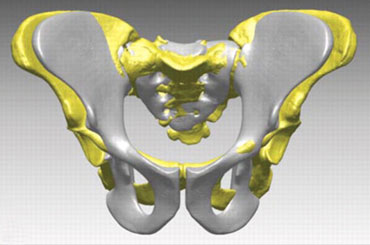

The pelvis of Ardipithecus shows the hominid could both walk upright and climb trees

Mauricio Anton/Science Source

A famous 4.4-million-year-old member of the human evolutionary family

was hip enough to evolve an upright gait without losing any

tree-climbing prowess.

The pelvis from a partial Ardipithecus ramidus skeleton nicknamed Ardi (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22) bears evidence of an efficient, humanlike walk combined with plenty of hip power for apelike climbing, says a team led by biological anthropologists Elaine Kozma and Herman Pontzer of City University of New York. Although researchers have often assumed that the evolution of walking in hominids required at least a partial sacrifice of climbing abilities, Ardi avoided that trade-off, the scientists report the week of April 2 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The pelvis from a partial Ardipithecus ramidus skeleton nicknamed Ardi (SN: 1/16/10, p. 22) bears evidence of an efficient, humanlike walk combined with plenty of hip power for apelike climbing, says a team led by biological anthropologists Elaine Kozma and Herman Pontzer of City University of New York. Although researchers have often assumed that the evolution of walking in hominids required at least a partial sacrifice of climbing abilities, Ardi avoided that trade-off, the scientists report the week of April 2 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Ardi

evolved a solution to an upright stance, with powerful hips for

climbing that could fully extend while walking, that we don’t see in

apes or humans today,” says Pontzer, who is also affiliated with CUNY’s

Hunter College. Ardi’s hip arrangement doesn’t appear in two later

fossil hominids, including the famous partial skeleton known as Lucy, a

3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis.

Ardi’s lower pelvis is longer than that of humans, which led some researchers to argue that Ardipithecus mainly climbed in trees and walked slowly with bent knees and hips, or perhaps not at all. But the new study shows it “would not have impeded its ability to walk upright in a humanlike fashion,” says paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Unlike other hominids and living apes, Ardi’s upper pelvis is positioned behind the lower pelvis, enabling a straight-legged gait, Pontzer and his colleagues find. An evolutionary reorienting of the pelvis in that way enabled back muscles to support an upright spine, Ward suggests.

A relatively large gluteus maximus works with hamstring muscles to push humans into a straight-legged stance. Ardi may have had a small rear-end muscle for her size, making a forward-positioned lower pelvis especially critical for walking, Pontzer says.

Using previous data from present-day humans, chimps and monkeys, Pontzer’s group documented a relationship between the shape and orientation of the lower pelvis and the energy available for a range of motions involved in walking and climbing. They used those findings to examine fossil pelvises of Ardi, Lucy and a 2.5-million-year-old Australopithecus africanus. No other fossil hominids from that long ago included a pelvis complete enough for analysis.

The researchers also evaluated a nearly 18-million-year-old fossil pelvis from an African ape, Ekembo nyanzae.

A. afarensis and A. africanus displayed pelvic arrangements for upright walking, but not for Ardi’s apelike climbing power. In particular, the lower pelvis of the two Australopithecus species was nearly as short as the walking-specialized lower pelvis of people today. E. nyanzae’s pelvis was specialized for climbing, as in modern apes and monkeys. Its long, straight pelvis enabled walking with bent hips and knees.

The new study coincides with previous evidence that Ardi’s lower back was flexible enough to support straight-legged walking, says paleoanthropologist Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University in Ohio. Lovejoy, who led an initial investigation of Ardi’s lower-body bones, has long contended that ancient hominids had a humanlike gait (SN: 7/17/10, p. 5).

“A. afarensis and A. africanus walked much like we do, and for the most part that goes for Ardi as well,” Lovejoy says.

Ardi’s unusual mix of walking and climbing abilities spurred the evolution of hominid bodies geared toward minimizing lower-limb injuries, Lovejoy proposes. Ardi’s long lower pelvis and apelike, opposable big toe were replaced in Lucy’s kind by a short lower pelvis connected to smaller hamstring muscles, a humanlike big toe and a fully developed arch (SN: 3/12/11, p. 8).

Those changes made climbing harder for A. afarensis, but stabilized its upright stance, helping to prevent foot injuries and hamstring tears when stopping suddenly or accelerating quickly, Lovejoy says.

Ardi’s lower pelvis is longer than that of humans, which led some researchers to argue that Ardipithecus mainly climbed in trees and walked slowly with bent knees and hips, or perhaps not at all. But the new study shows it “would not have impeded its ability to walk upright in a humanlike fashion,” says paleoanthropologist Carol Ward of the University of Missouri in Columbia.

Unlike other hominids and living apes, Ardi’s upper pelvis is positioned behind the lower pelvis, enabling a straight-legged gait, Pontzer and his colleagues find. An evolutionary reorienting of the pelvis in that way enabled back muscles to support an upright spine, Ward suggests.

A relatively large gluteus maximus works with hamstring muscles to push humans into a straight-legged stance. Ardi may have had a small rear-end muscle for her size, making a forward-positioned lower pelvis especially critical for walking, Pontzer says.

Using previous data from present-day humans, chimps and monkeys, Pontzer’s group documented a relationship between the shape and orientation of the lower pelvis and the energy available for a range of motions involved in walking and climbing. They used those findings to examine fossil pelvises of Ardi, Lucy and a 2.5-million-year-old Australopithecus africanus. No other fossil hominids from that long ago included a pelvis complete enough for analysis.

The researchers also evaluated a nearly 18-million-year-old fossil pelvis from an African ape, Ekembo nyanzae.

A. afarensis and A. africanus displayed pelvic arrangements for upright walking, but not for Ardi’s apelike climbing power. In particular, the lower pelvis of the two Australopithecus species was nearly as short as the walking-specialized lower pelvis of people today. E. nyanzae’s pelvis was specialized for climbing, as in modern apes and monkeys. Its long, straight pelvis enabled walking with bent hips and knees.

The new study coincides with previous evidence that Ardi’s lower back was flexible enough to support straight-legged walking, says paleoanthropologist Owen Lovejoy of Kent State University in Ohio. Lovejoy, who led an initial investigation of Ardi’s lower-body bones, has long contended that ancient hominids had a humanlike gait (SN: 7/17/10, p. 5).

“A. afarensis and A. africanus walked much like we do, and for the most part that goes for Ardi as well,” Lovejoy says.

Ardi’s unusual mix of walking and climbing abilities spurred the evolution of hominid bodies geared toward minimizing lower-limb injuries, Lovejoy proposes. Ardi’s long lower pelvis and apelike, opposable big toe were replaced in Lucy’s kind by a short lower pelvis connected to smaller hamstring muscles, a humanlike big toe and a fully developed arch (SN: 3/12/11, p. 8).

Those changes made climbing harder for A. afarensis, but stabilized its upright stance, helping to prevent foot injuries and hamstring tears when stopping suddenly or accelerating quickly, Lovejoy says.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Observação: somente um membro deste blog pode postar um comentário.